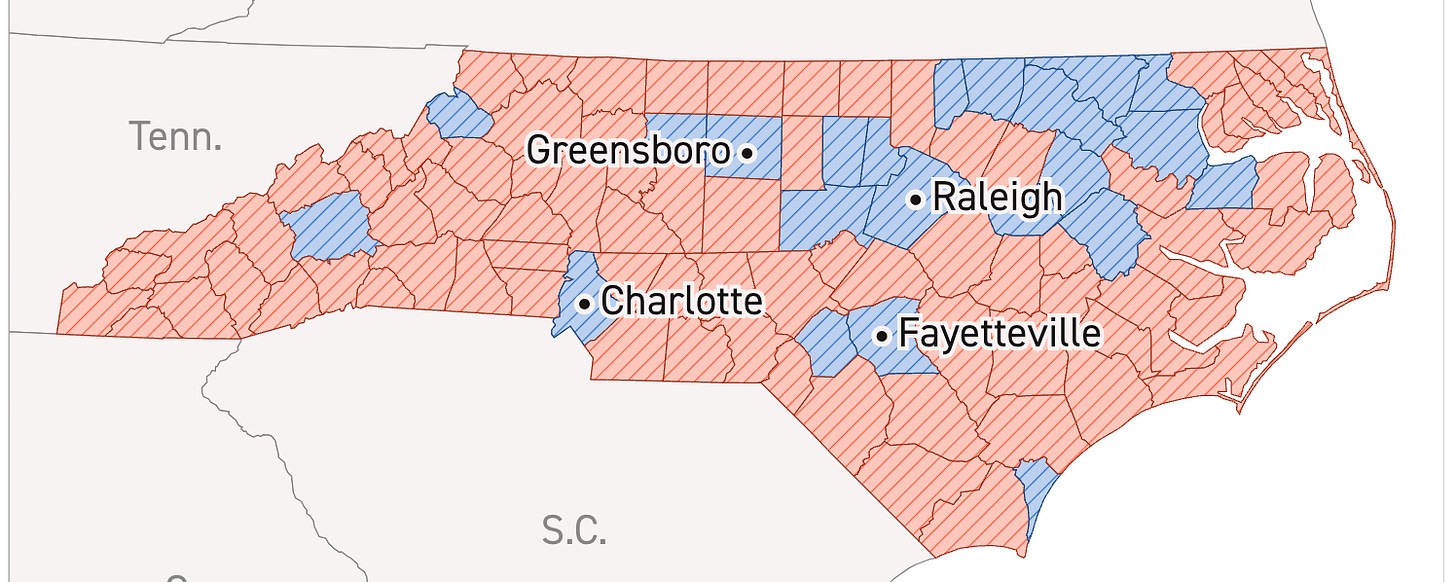

On my way to a conference this week, I drove through a deep red, military heavy, and economically depressed region where huge signs stood on rural front yards exclaiming, “Thank you Jesus for Donald Trump.” That is to say, I took a drive through eastern North Carolina where it several counties turned out ~70% vote for Trump.

The scenery of the drive resonated as I listened along to a 2018 audiobook by political scientist, Francis Fukuyama, proposing that the fragile state of liberal democracy in the United States and Trump’s initial rise to the presidency is driven by deprivations of dignity and a politics of resentment. This, in turn, creates an environment for the growth of religious nationalism.

The now familiar line of reasoning discussed for quite some time by those far wiser than me) is that the non-college educated working class feels ostracized and unseen by a the social and economic elite who have created complex, technocratic governing regimes and modes of production that fail to respond to the needs and interests of those with less education and different value prioritizations.

As David Brooks recently put it in describing the nation’s re-scrambling of production in place and form, “Donald Trump is a monstrous narcissist, but there’s something off about an educated class that looks in the mirror of society and sees only itself.”

These are the narratives, visuals, and thoughts that occupied my mind as I arrived at the conference where, upon registration, I was promptly invited to make origami, filling my bucket with respect given that I braved the dreaded mild awkwardness of small talk to be there.

Throughout the day’s sessions, I lost count of how many times speakers explained some such problem’s cause or significance as “because of climate change” simultaneously misconstruing the state of knowledge and therefore, the nature of the problem.

The rhetorical device sounds like it is invoking science, but more readily betrays speakers’ own knowledge limits. None of us are experts in everything.

The unspoken message is therefore that if want to engage in these areas of policy you need the technical credentials to warrant respect for an alternative problem framing because legions of bureaucrats doing the work of government are falling in line the the reigning technocratic order.

In one flick of a phrase the social trends, shifting demographics, and conflicts among interests are made invisible.

One of threads to come out of post election commentaries about what the results reveals about the state of the Democratic party concerns the past, present, and future role of experts in policymaking.

Don Kittle writing at Persuasion, finds that both the left and the right undermine the governments ability to harness expertise effectively:

So from the right we have complaints about accountability. From the left we have proceduralism that hinders the ability of experts to get the people’s work done. This crusade is pushing the government away from expertise, which will only further erode the trust of people in government and make it impossible to get government’s work done.

Kittle recounts a lengthy history of America’s efforts to engage experts while also maintaining accountability of policymakers and experts, and finds that today:

the basic question of experts in government—how much discretion they ought to have, how much power they ought to wield, how large a role the government ought to have in our lives. This is the most intriguing and most fundamental constitutional struggle about governance for our time.

Government needs experts and importantly, it needs experts that are not just loyalist to a party or a leader. Rather, experts use their knowledge and skill to support policy implementation in a way that is as impartial as possible.

Public facing leaders of institutions of science appear, at best, obtuse to all of this. President of the National Academies of Science, Marcia McNutt, writes publically that

scientists need to better explain the norms and values of science to reinforce the notion—with the public and their elected representatives—that science, at its most basic, is apolitical. Careers of scientists advance when they improve upon, or show the errors in, the work of others, not by simply agreeing with prior work. Whether conservative or liberal, citizens ignore the nature of reality at their peril.

Note how the last sentence- the public must listen to scientists- contradicts the starting claim that science is apolitical. The claim that careers move forward by showing how others are wrong is disingenuous to the extent to which scientific careers advance by upholding dominant ideas and that careers are made very difficult by illustrating the faults of politically expedient narratives. Hence, the falsehood in the claim of an apolitical science.

At worse, leading scientists spread a reckless and insulting narrative no less damning than that overflowing from other political extremes.

The crisis facing experts of all stripes is apparent in the conference because it represented a simple cross section of experts in government and academia, along with their students and apprentices. These are people with jobs and busy lives, doing their best to be good and do good.

Unpacking the politics of embedded assumptions in technological processes doesn’t just require a certain realm of expertise, it requires time which is a limited resource for many. It also carries the air of being too theoretical and thus insignificant.

But it is these assumptions buried deep in technological practice where ideologies thrive, power is grabbed, and swaths of the population are unseen.

One small example…

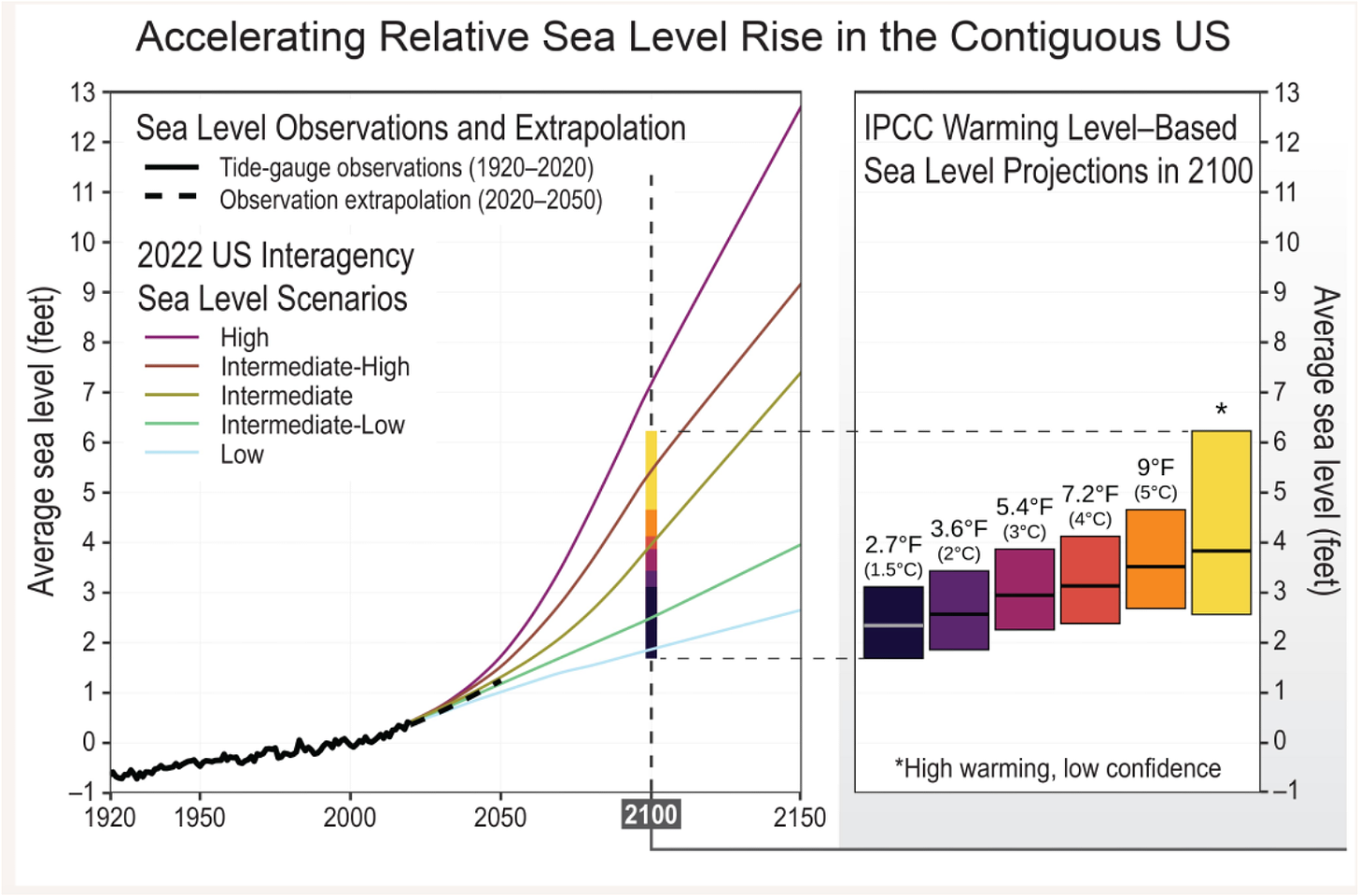

In October, the Science Panel who are advisors to North Carolina regulators of coastal development, released the final version of its third iteration of sea level rise (SLR) scenario projections for the state. And for the third time the Science Panel neglected to help policymakers understand underlying socio-economic assumptions of the emissions scenarios behind the SLR projections for global mean sea level.

This shortsightedness matters on multiple levels.

First, is the obvious: informing policymakers and giving them a fair assessment of the scope of choice.

But others reasons include providing:

the public with a trustworthy document useful for holding policymakers accountable

experts in other disciplines useful guidance to orient inquiry on related matters

material useful in college classrooms for educating future experts and advisors

Done well, science advice can help prevent the stagnation of reason among our diverse range of experts providing opportunity for many views and values.

But it is not going well.

The Science Panel’s draft report from April primary regurgitated talking points from the executive summary of the 2022 Federal government’s sea level rise scenario report.

And so, in response to public comment on the draft report, the Science Panel found itself defending the Federal government’s methods and rational- an odd place for state science advisors to find itself.

Science Panel explains the Federal scenarios:

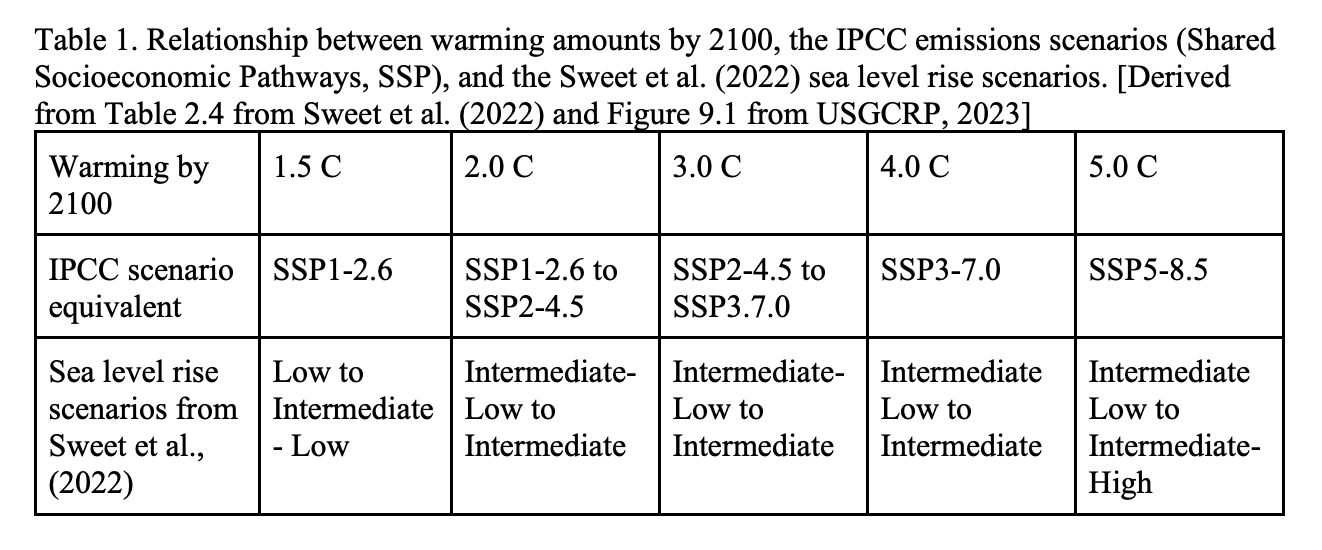

The five sea level rise scenarios, which are “related to but distinct from the emissions pathway scenarios” (Sweet et al. 2022, p. 10) in the IPCC AR6 Synthesis Report (IPCC, 2023), are based most directly on how much warming occurs by 2100 (Table 1; Appendix Figure 1). However, the sea level rise scenarios cannot be related one-to-one to the warming scenarios because of uncertainties, which mean that different amounts of sea level rise could occur for the same amount of warming (USGCRP, 2023).

Appendix Figure 1 is from the 5th National Climate Assessment1, a report that is itself partly a product of the Federal SLR scenarios and engages several of the same individuals and their business and advocacy interests.

Decoupling warming scenarios (aka global warming levels) from anything going on in real life may be useful for an earth modeler interested in understanding the outcomes of a range of temperature changes. But it is not helpful in a policymaking context.

Because the Science Panel refused to engage with the underlying socio-economic assumptions of the “IPCC scenario equivalent” for the temperatures used to drive federal SLR scenarios, the Science Panel produced a report that gives remarkably little insight.

Worse, it inadvertently upholds and leaves unquestioned the methodologies preferred by well positioned experts that have pursued a decoupling of temperature (and radiative forcing) from underlying socioeconomic rationals during the Biden Administration2.

Most significantly, the Science Panel does not fulfill its charge to “review of any new and significant scientific literature and studies that address the range of implications of sea level rise.”

Without a doubt, the most significant and widely discussed revelation related to climate and SLR since Science Panel’s last report in 2015 is the extent to which the most used scenarios are outdated.

The Science Panel has therefore made the state institutions vulnerable to the incoming political regime that has, in the past, displayed contempt towards expertise and, in the present, shown a keen awareness of how deeply divorced narratives of climate change are from the underlying knowledge base.

The Federal SLR reports are tied to the National Climate Assessment process, which is directly overseen by the White House. The bulk of the next reporting cycle will take place under the Trump administration. We should expect changes in how scenarios are presented and discussed in the next report. The discussion is likely to conflict with the climate change reporting North Carolina has produced over the past many years. A situation that the Science Panel could have and should have prefaced.

To be sure, North Carolina is facing serious amounts of sea level rise that present significant infrastructure and political hurdles for managing a resilient coastal economy. This conclusion rests on simple extrapolation of observational data. Anthropogenic influence on the climate exacerbates the sea level rise problem.

Had the Science Panel presented an appropriate explainer in their SLR report it would have provided the state with advice that better stood the test of time, shifting political regimes, and simply, fulfilled its charge better by providing genuine expertise.

The problem of the North Carolina Science Panel’s report on Sea Level Rise speaks to fundamental questions about experts in policymaking that is rippling widely throughout society.

All of this matters in very serious ways. It matters for public trust. It matters for a continued role of experts in policymaking. It matters for the development of good policy that satisfies the value concerns of various publics.

It matters for ensuring a viable future for an American liberal democracy.

The Science Panel also says nothing about the history of the Federal SLR scenarios and the extent to which they became fixed over ten years ago, the nuances of the underlying methodology, or how they differ from those produced by the IPCC.

"...feels ostracized and unseen by the social and economic elite who have created complex, technocratic governing regimes and modes of production that fail to respond to the needs and interests of those with less education and different value prioritizations."

Fail to respond?

Howsabout ignore, or frequently worse, denigrate maybe?

That, to me, seems more the case these last eighteen years than any evident failure to respond.

Experts exist, but in several kinds.

The first is true to natural language, persons amongst the best of knowledge and experience in a particular field.

Another is nothing like the original meaning. Picking from a large population of persons working in a particular field, journalists and politicians designate the status of expert upon selected persons whose stance they intend to use to further personal and political advantage.

Then there is the real expert in the first sense who is well known and takes a stance on an issue which is way outside their speciality.

Sea level is something that can be measured. It is measured by many methods and some of those methods have been used for a very long time and produced precise records about the level at that location.

Real measurements like those can be compared. They show that the water level is rising very slowly in numerous places, falling very slowly in numerous places and not changing at all in others.

When looked at overall, it becomes clear that some of the sites are actually on rising land, some on land which is sinking and some are neither. These measurements and comparisons are not models and depend upon no theory for their absolute values. The next step is interpretation, and that comes from the knowledge of water as fluid or solid or vapour, the scientific intelligence and imagination of people and their reasoning abilities.

In 2024, based on the data, there is a very, very slow rise which began at the end of the last ice age.

Nothing to write home about. Not a global problem, maybe a local problem where the falling land level threatens to inundate built-up inhabited coastal land and vice versa.