As workers across America cleared out and signed off mid week for the Thanksgiving holiday and long weekend, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton and 10 other state attorneys general filed a lawsuit in Texas (hereafter as, Texas et al) alleging that three of the largest asset managers in the world- BlackRock, State Street, and Vanguard- violated the Sherman Act and the Clayton Act in a conspiracy to constrict the coal market in the name of climate change. By limiting coal production in the face of demand, the asset managers produced much higher profits.

The lawsuit is the latest move in fleshing out a “climate cartel” whereby investors are organized through several business coalitions to collectively pursue emissions reductions through forcing change in energy production and industrial practices. Attention has mostly focused on Climate Action 100+.

I can’t say whether the overall dynamics amount to antitrust violations. However, I do believe that what is being brought forward by Texas et al is indicative of the hubris and financialization of the climate movement, and the problems that arise when interests seek to circumvent the democratic policy process in favor of forcing society to meet assumptions embedded in models.

This past summer, a hearing of the U.S. House Judiciary Subcommittee on the Administrative State, Regulatory Reform, and Antitrust examined Climate Action 100+ and a small activist investment firm. Key testimony was provided by Mindy Lubber, CEO and president of the sustainable finance nonprofit, Ceres, and member of the steering committee for Climate Action 100+, which Ceres helped found and manage.

A reoccurring point in Lubber’s response to legislators was that signatories to Climate Action 100+ commit to shared information and methodologies for assessing climate risk.

As I wrote then,

Following Lubber’s explanation, Climate Action 100+ commits investors to adopt “distinct analytical methodologies” and climate risk metrics. The underpinning of coordinated behavior among investors is their shared technical assumptions and methods about climate financial risk.

By committing to the methodology, companies are committing to a shared vision for society and a collective way of organizing investments.

The methodological practices include the use of scenarios consistent with the International Energy Agency (IEA) for Net Zero Emissions by 2050 or those of the P1 pathway1 used by the IPCC for limiting warming to 1.5C by 2100.2

The schematic and narrative of the P1 pathway is shown below. In addition to a rejection of carbon capture and sequestration technology to meet emission goals, the pathway requires a 78% reduction in primary energy from coal by 2030 and a 97% reduction by 2100 (relative to 2010 levels).

Now, because IPCC reports tend to be complicated, the P1 pathway is really the “low energy demand” (LED) scenario discussed elsewhere in IPCC reporting and documented in detail here. The gist of the LED is that energy demand by 2050 is reduced to around 40% lower than today despite rises in population, income and activity. Obviously, the LED scenario engages profound social and technological change.

Similarly, IEA Net Zero Emission by 2050 scenario envisions a world where the total energy supply from coal reduces around 60% by 2030, and is non-existent beyond plants without carbon capture technologies by 2050. This transformation of the energy sector also requires dramatic social and technological change where 55% of emissions reductions require consumer involvement in things like buying an EV and another 8% of emissions reductions stem from activities like flying less.

I bring all this up because it is important to acknowledge that those committed to the Climate Action 100+ methodology are also committed to an upheaval across society managed through the will of investment firm CEOs with the assumption that the citizenry and civic order will quietly abide.

Let’s take a look at Texas et al.

Clayton Act of 1914 is a core component of US antitrust legislation that limits unlawful restraint on trade and monopolistic power. Texas et al claims that the asset managers stake in coal companies bring “under one control the competing companies whose stock it has thus acquired” and that they have used this control to decrease coal production in the face of high energy demand resulting in higher costs and thus higher profits.3

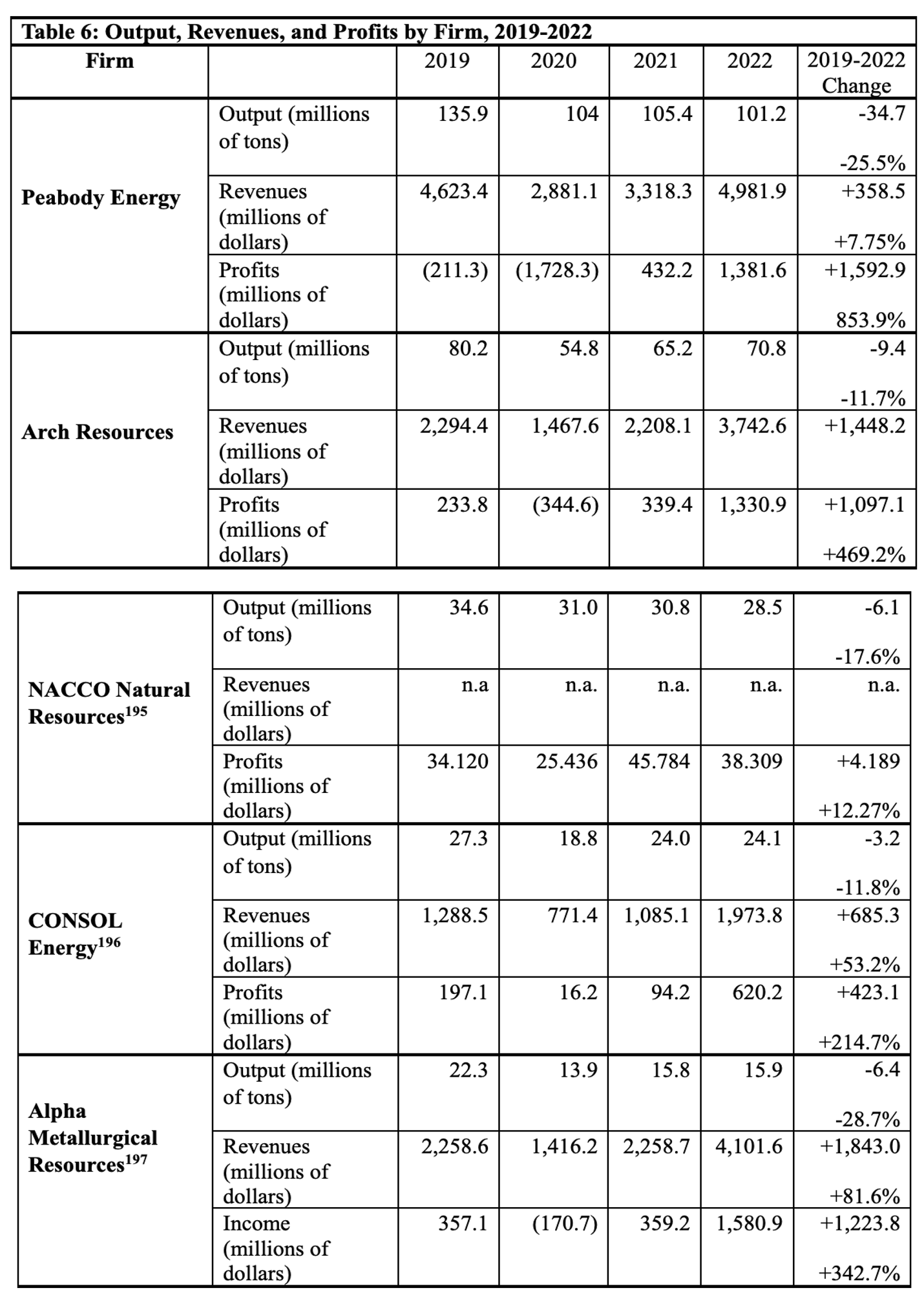

The Defendants- the three asset managers- have a significant collective ownership stake in US coal producers. Of the two largest US coal producers, Peabody Energy and Arch Resources, the three asset managers have stakes of 30.43% and 34.19%, respectively. The companies listed in the Complaint Table 1 account for 46% of total domestic coal production.

Furthermore, writes the Plaintiffs,

Defendants each publicly announced their commitment to use their shares to pressure the management of all the portfolio companies in which they held assets to align with net zero goals. Those goals included reducing carbon emissions from coal by over 50%. Rather than individually wield their shareholdings to reduce coal output, therefore, Defendants effectively formed a syndicate and agreed to use their collective holdings of publicly traded coal companies to induce industry-wide output reductions.

In turn, Plaintiffs in Texas et al seek to demonstrate real-world intent to restrain trade and act in a coordinated manner by citing the public facing marketing and advocacy material announcing climate commitments by asset managers and their advocacy initiatives. There are many examples.

This advocacy/marketing is complimented by public claims that, through groups like Climate Action 100+, investors have enough sway to replace corporate management with leadership that will uphold the ideals embedded in its choice methodologies:

Resistance by management was futile because, as Ms. Lubbers4 continued, “[i]f companies aren’t willing or able to respond to the challenge of moving towards a net zero transition, we will look for new leadership. … There may be board directors who don’t feel compelled or have the expertise to get this transition done – but they must then make way for those that do. This is concentering [sic] minds in boardrooms and across the investor community and is a new, welcome dynamic to engagement and stewardship.”59

The same groups that bring together the Climate Action 100+ initiative also created the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative (NZAM). According to Texas et al:

The signatories to the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative specifically commit to phasing out coal investments: “Notably, this includes immediately ceasing all financial or other support to coal companies* [sic] that are building new coal infrastructure or investing in new or additional thermal coal expansion, mining, production, utilization (i.e., combustion), retrofitting, or acquiring of coal assets.”65

Given laws of supply and demand, constraining coal supplies increases the cost of coal. So, at least as the Plaintiffs tell it, investors make a bunch of money while they force society to rapidly change their energy sources. Table 6 (reproduced below) shows declining coal production, increasing revenues, and substantial increases in profits.

The Plaintiffs in Texas et al argue that the data and trends they provide are not due to other contextual factors like COVID-19 and rapid energy demand shifts from the war in Ukraine.

They conclude,

In sum, the data demonstrates that publicly held domestic coal producers were not responding to the laws of supply and demand. They were instead answering to Defendants, who acquired substantial shareholdings in each of these companies, possessed the power and the will to reduce the companies’ production of coal, and made public commitments to vote management out of office if they failed to reduce coal production and publicly disclose both reduction targets and the data establishing compliance with those targets. What happened next was economically predictable: Defendants’ acquisition of shares in the Coal Companies caused a substantial reduction in competition between those firms

It will be interesting to see how this plays out. Here are some things I’m curious about:

Overall US coal production been in decline or stagnant for a long time now and for a variety of reasons. It would be good to understand how the five year trend analyzed in Texas et al differs from background trends, and how this plays out in the stated relevant markets for South Powder River Basic Coal and thermal coal .

Because privately held coal companies are used as the counterfactual in the complaint it would be interesting to know if public and privately held coal companies respond in the same way to the background trends in coal production.

Finally, I am wondering how much of a pandora’s box is opened up here regarding collective allegiance to model assumptions, and the limits of federal antitrust jurisdiction. I can think of examples where climate change advocacy beckons the use of specific views on climate risk which in turn embeds preferred assumptions across a sector.

The complaint in its entirety is below.

Update 12/27/2024: A friend pointed me to the big debate about the common ownership theory embedded in the complaint.

IEA refers to scenarios. IPCC refers to pathways, but admits that the meaning of the term is now muddled. Meanwhile, what the IPCC calls the P1 pathway, the authors of P1 which is really LED, refer to it as a scenario.

Also worth a mention, the methods include Disclosure practices as outlined by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial which include, analyzing transitional and physical climate risks under different temperature targets and emissions accounting via the scopes. And the GHG Protocol which originated the emission “scopes.”

I don’t cover it here but the lawsuit also alleges that BlackRock deceived its investors:

Rather than inform investors that it would use their shareholdings to advance climate goals, BlackRock consistently and uniformly represented its non-ESG funds would be dedicated solely to enhancing shareholder value. But as detailed below, BlackRock routinely violated its pledge to investors, using all its holdings to advance its climate goals and—as most relevant here—promote the objectives of its output reduction syndicate.

I was revisiting the bankruptcy of Sears the other night and how it was basically an act of Vulture Capitalism with the same hedge fund that drove K-Mart into the ground in 2002, buying and then looting Sears.

The point being I was pondering the concept of Vulture Capitalism, in which a group gains ownership of what is nominally a public company and then loots the wealth accumulated by the company for their own use.

How much does the climate movement parallel an act of Vulture Capitalism? These jokers have grabbed control of the levers of state and now use them to vote themselves massive subsidies from the public, while restructuring economies so that necessary public goods become volatile and expensive creating a perfect environment for the profiting of speculators. Of course, all such profits ultimately are looted from the pockets of consumers.

Plural of "attorney general" is "attorneys general."