On April 8th, yet another Trump EO rolled out: Protecting American Energy from State Overreach targeting state that have

enacted, or are in the process of enacting, burdensome and ideologically motivated ‘climate change’ or energy policies that threaten American energy dominance and our economic and national security.

Last fall, I wrote a bit about the Vermont’s Climate Superfund law.

The EO further states concerns that

States have also sued energy companies for supposed ‘climate change’ harm under nuisance or other tort regimes that could result in crippling damages.

The EO directs the United States Attorney General to identify and stop,

any such State laws purporting to address “climate change” or involving “environmental, social, and governance” initiatives, “environmental justice,” carbon or “greenhouse gas” emissions, and funds to collect carbon penalties or carbon taxes.

The same day, Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick announced a $4 million funding cut to Princeton University cooperative institutes with NOAA because they “are no longer in keeping with the Trump Administration’s priorities.” Elsewhere, it was reported that the Trump Administration’s seeking to “eliminate all funding for climate, weather, and ocean laboratories and cooperative institutes.”

Lutnick gave additional reasons for cuts to specific programs including the Cooperative Institute for Modeling the Earth System (CIMES):

This cooperative agreement promotes exaggerated and implausible climate threats, contributing to a phenomenon known as “climate anxiety,” which has increased significantly among America’s youth. Its focus on alarming climate scenarios fosters fear rather than rational, balanced discussion.

The statement legitimizes “climate anxiety” as warranting policy response with the decision to end (some or all) climate change research. Predictably, reporters jumped all over this cause and effect argument.

There is limited agreement on the meaning of climate anxiety and ways to measure it. The term has a long lead up both in its roots to earlier ideas of “solastalgia” (nostalgia induced distress from environmental change), “ecological grief,” and in the mobilization of psychology researchers towards researching various facets of human behavior in respect to climate change, broadly construed.

Climate anxiety is treated as a synonym to the broader “eco-anxiety”, a term presented to the world in 2017 through an enduring partnership between the American Psychological Association and EcoAmerica.

Much of this work came from those engaged with the American Psychological Associated Division 34: Society for Environmental Population and Conservation Psychology. Writing in 2000, a history of the division explains that its origins with concerns about population growth and ecological degradation weighs heavily on the work of its members.

It is unclear to me when the term climate anxiety was first used but it’s rapid popularization of the term began around 2020 heralded by a few leading voices.

Professor Susan Clayton has been particularly influential leading several reports by APA and APA-EcoAmerica on the topic, creating a commonly used metric to measure climate anxiety in individuals, and establishing clinical use of the term through publication in the Journal of Anxiety Disorders. She was also a lead author on the IPCC AR5 where climate change and mental health made its way into the WGII and WGIII reports.1

In 2021, the term really took off through highly publicized report in The Lancet Planetary Health led by Caroline Hickman, a researcher in England, and coauthored by Clayton and others. I have written a bit on these reports.

The discourse around climate anxiety has a strong recruitment vibe to it and frequently evokes extreme weather disasters and crisis framings. It’s narratives target children and young adults directing them to advocacy and conveying the strange sense that something is being done to them.

In effect, it confirms and re-enforces the message put forth by James Hansen and colleagues that existing energy policies are an intergenerational injustice- work that according to Hansen is “the basis for federal and several state cases that have been filed, and which are now making their way through courts.”

The way climate anxiety is invoked and discussed strikes as a form of anchoring to create a predisposition towards a certain attitude among younger generations. The greatest predictor of “climate anxiety” is someone who is already looking for dramatic information about climate change; they are already predisposed.

According to a statement attributed to Hickman, “If you look at any research in mental health with regard to children, the only thing you don’t do is stop talking about the thing that’s frightening children.”

I am not a mental health professional and we all have our own parenting styles. However, there seems to me, a vast difference between responding to children’s questions about the world and running non-stop advocacy messaging in the background of daily life, if not also in the classroom.

In a recent meeting of the National Academy of Science various interests- researchers, journalists, legal professionals, and McKinsey, discussed the applications of extreme event attribution studies.

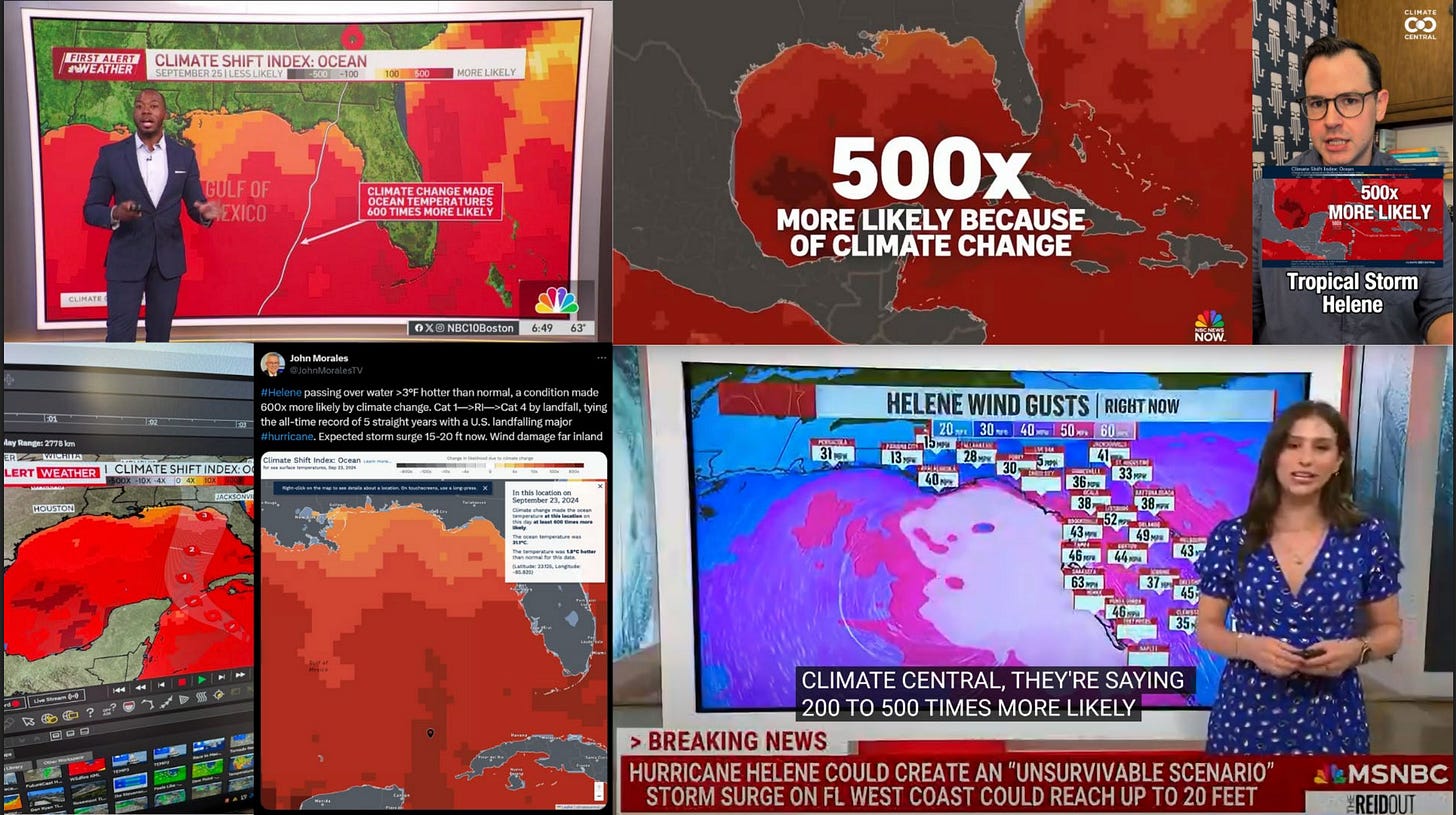

The slide below is from the presentation of Climate Central, a ring leader of the extreme event attribution studies underpinning the state policies that Trump rails against in his EO.

At least most of the imagery in the slide is made by Climate Central. It’s use by mainstream news outlets means that it is being shown in homes across America. Presumably, many of those homes have children and young people in them.

Interestingly, the Hurricane Helene EEA analysis featured throughout the Climate Central presentation to the National Academy of Science was coauthored by a CIMES researcher and given a feature news piece at NOAA.

This is a serious spectacle.

Final thoughts:

The complex and serious problems at the interface of science and politics are being passed off as a matter of rooting out buzzwords as illustrated by the Trump EO. However, the scientific enterprise is sufficiently complex that the forms of technical activity the public may want to move away from- perhaps for very good reason, are not easily parsed from its valuable research infrastructure.

There is a need for critical examination and convincing narratives about the intentions for US research moving forward. Currently, there is no narrative and this results in the deepening of distrust and division.

Already, nations are eying the tumult in the United States as an opportunity to get a leg up in research, development, and in policy areas heavily tied to science. European nations are actively recruiting American researchers promising them a “Safe Place for Science.”

The result is everyone else’s cohesive narrative around science- no matter its merit- against America’s increasing disarray and lack of trust.

Previously, Clayton published an analysis in Nature of notable climate researchers who wrote letters about their feelings of despair for the project, “Is This How You Feel?”

The shark has been jumped. Now we watch them scramble on the slide down from on high.