Is an Equitable Carbon Offset Industry Possible?

The C-Quest Capital Scandal and Western Elitism

By Jessica Weinkle

On October 2nd, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) announced it had filed and settled a cease-and-desist order against C-Quest Capital, a firm selling carbon offsets. On the same day, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) filed a complaint against the firm, and the Department of Justice (DOJ) announced criminal charges against C-Quest Capital’s former CEO, Ken Newcombe. All agencies made accusations of fraud.

These legal proceedings signal the real-world ramifications of the questionable assumptions underlying emissions credit schemes. Supporters promised such offset projects, once popular, would lead to not just reduced emissions, but also environmental preservation and sustainable development. In reality, they did neither.

For his part, Newcombe was a key architect in developing a carbon market and a carbon offset industry. He spent nearly 30 years at the World Bank, where he developed the bank’s carbon trade and piloted the Global Environmental Facility. Newcombe moved on to the private market, developing carbon credit trading as a private business activity, founding C-Quest Capital and developing one of the market’s NGO regulators, Verra, the world’s largest organization that vouches for the quality of carbon credits for offsetting emission.

Newcombe’s central role in developing carbon trading places him at the forefront of the fundamental misframing of climate change as a problem to be resolved through market-driven trading mechanisms that yield sustainable development as a byproduct.

Following the indictment, media coverage centered on the problems that manipulation of carbon accounting practices presents for investors and global efforts to reduce emissions. Lost in this perspective is the market’s targeted exploitation of the poor.

C-Quest Capital’s cookstove carbon projects is a perfect example of this classist exploitation. Calculating carbon credits from cookstoves that produce lower emissions is a speculative practice resting on assumptions of avoided emissions. At base, the grand accomplishment elite financiers claim in cookstove projects is not poverty alleviation at scale, or even improved infrastructure, or energy access. They are simply providing the poorest people on earth with a stove that uses fewer sticks.

There’s far more promise for carbon markets and carbon management to be found in projects on standardizable carbon removal technologies. And it is here that some are hopeful that legal action against Newcombe can further support more worthwhile industrial and market expansion.

The CQC Scandal

Billions of people in developing countries depend on cooking fuels that produce poor air quality and cause premature death. These unhealthy fuels also produce carbon emissions. Popular cookstove carbon offset projects promise to reduce carbon dioxide emissions and improve human health by distributing more fuel-efficient stoves.

The unraveling of the C-Quest Capital (CQC) cookstove program—one of the largest in the world—began in mid-2023 when several C-Quest employees raised concerns about discrepancies in the reporting data for the cookstoves projects. Then, in December, an exposé by a British news station created further intrigue. In interviews with users in Malawi, British reporters found that people liked the cookstoves because they produced less smoke but the stoves, made of a combination of metal and clay, broke easily. Few remained in use for longer than a year, a fact that ran counter to the numbers on deployed cookstoves in CQC’s reporting.

Months later, in early 2024, a special committee of the CQC Board of Directors initiated a self-imposed legal investigation of its accounting methods and replaced Newcombe as CEO. CQC then reported to Verra that it had over-issued millions of carbon credits from clean cookstove carbon projects.

According to the DOJ indictment, Newcombe had committed CQC to install about 1 million stoves per year between 2021 and 2023 while raising money through special purpose vehicles. In an effort to deliver the carbon credits CQC had promised, the stove installation team started cutting corners and notified Newcombe that the project was suffering from operational issues.

At the same time, the company’s calculations for emissions reductions relied primarily on the reported number of installed cookstoves in place and operational during a given time frame and the reduced fuel used by the cookstove as compared to their conventional methods. Data came from sample surveys and was extrapolated out across the stove recipient population. In order to meet the special purpose vehicle’s contractual obligations, Newcombe inflated the number of carbon credits that the cookstove projects produced. This practice was internally referred to euphemistically as “manag[ing]’ the data.”

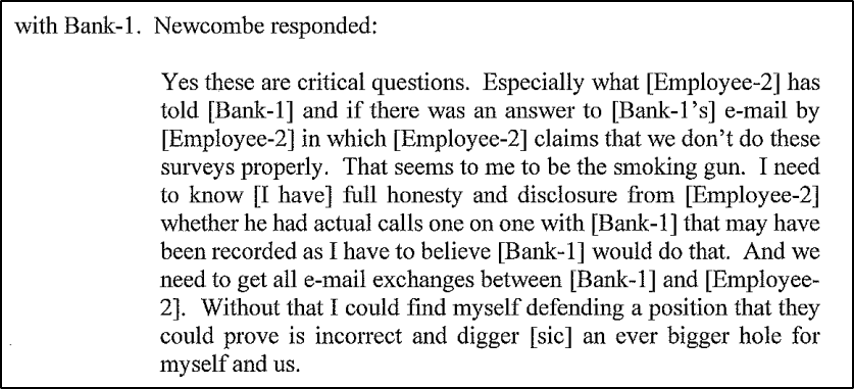

Survey data indicated that the stoves reduced fuel use by only half of what CQC promised. According to the DOJ, Newcombe’s response to that information was that CQC had needed a bigger target “to make the basic economics of the deal work.” So, Newcombe and other personnel developed fraudulent survey forms.

Further, when personnel would find households that were no longer using the stoves, they “took steps to falsely and misleadingly increase the reported number of cookstoves in place and operational,” according to the CFTC. At times, survey personnel were directed to simply make up data. The DOJ, for example, reports on a WhatsApp chat between a CQC executive and an employee managing survey data. The employee wrote:

“during an inspection of a house in which they had previously installed a stove, they discovered that ‘[t]he house is no longer there[.] [T]he beneficiary lived in a makeshift structure.’”

The executive responded:

“Hmm, instead of losing all the carbon as a result of getting 19 out of 20 samples, can we… build a stove in a nearby house, and say the person moved but gave the stove parts… to another household…”

The federal legal actions against CQC are billed as the first coordinated multi-agency action directed at carbon markets. It is also the first case directly tied to the CFTC’s Environmental Fraud Task Force, which was created in June 2023 to “combat environmental fraud and misconduct in derivatives and relevant spot markets.” (The Task Force did wet its feet in an earlier case characterized as a “classic Ponzi scheme” that involved crypto currency related to carbon offsets.)

Major law firms are loudly sounding warnings that the CQC case is the start of efforts to root out environmental bad actors in financial markets. The mega firm, Holland & Knight, states, “we expect [carbon markets] to remain an area of focus in a potential Kamala Harris administration.”

Though I don’t see why a Donald Trump administration wouldn’t want to take a go at this train wreck too.

Financialization of Poverty

For years, reporting on developments in the carbon credits market has been filled with stories of dramatic land grabs, environmentally dubious hustles, get-rich-quick schemes, spurious consent, and overall ineffectiveness.

The British news report on the CGC’s cookstove controversy incidentally highlights the elitism inherent in the ideology of the carbon credit market. The report opens with footage of men illegally collecting wood from the forest, piling it high on a bicycle, and carefully walking it four miles to town to sell for cooking. “You might wonder,” says a newscaster standing in front of a fancy screen, “is the carbon from my long haul flight really being offset? In particular, is it being offset by enough people in developing countries being encouraged to change from cooking on open fires to more climate friendly stoves.”

Indeed, how dare those poor Malawians burn illegal wood to cook beans when we have intercontinental trips planned by jumbo jet?

The merit of the carbon credit market is frequently sold on its ability to deliver positive social and environmental benefits, not just manage carbon emissions. For instance, the Olympic and Paralympic Games Paris 2024 purchased 1.3 million carbon credits, through the carbon credit platform Abatable, with promises to empower women, protect biodiversity, and expand renewable electricity across an enormous range of countries including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guatemala, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, and beyond.

Yet, even those in finance take such claims with a large grain of salt.

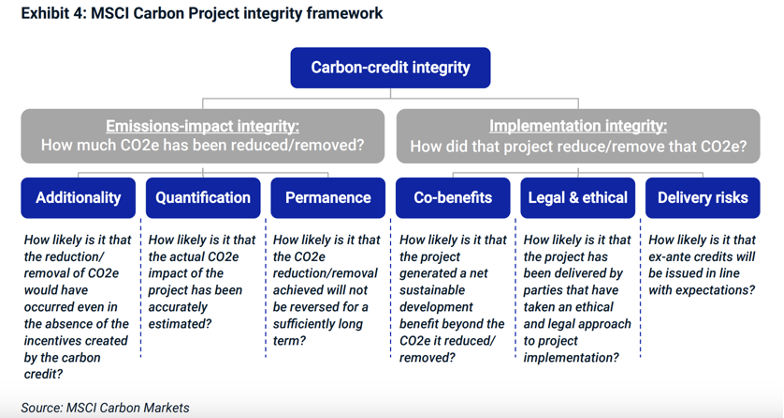

The financial firm MSCI has found that only 5% of 4,000 carbon credit generating projects on the market are considered high integrity. Their rating framework uses six metrics in two categories:

1) The effectiveness of the project in reducing emissions beyond what would have

happened in the absence of the project

2) Environmental/social impacts including environmental and social safeguards and

general sustainable-development impacts.

The overall integrity rating score is calculated using a weighted formula where emissions integrity is worth a total 70% and implementation integrity is worth 30%. So, carbon credits are generally sold with lofty claims of social and economic benefits, but are judged on their representation of an actual tonne of carbon dioxide emissions.

That carbon credits are expected to represent a certain amount of carbon emissions seems patently reasonable. What is deeply problematic is that they are also expected to achieve sustainable development goals because they are neither sustainable nor developmental.

The carbon offset industry treats human dignity and the economic development of poor nations as a “co-benefit” in a virtual signal marketing scheme targeting the buying power of the bourgeois hipster class while heading-off their characteristic ability to mobilize shame campaigns against industry.

The problem in offsets is not greenwashing, per se; it is a fundamental misrepresentation of the levers that produce sustainable development. Carbon offset projects are poorly suited for economic development because they target nations that need fossil fuel intensive solutions for development. They need roads, cold-storage systems, fertilizer and, yes, gas for cooking. And the technologies and efficiencies that enable environmental sustainability are made possible by the wealth gained through economic development.

A new report by The Breakthrough Institute demonstrates the extent to which developing countries- under pressure from rich nations- favor climate mitigation projects over climate adaptation projects. But it is the adaptation projects: the roads, buildings, refrigerators, and reliable baseload energy, that provide a path toward sustainable development, not the clay stoves.

A Carbon Capture Industry for All

Carbon credit markets have not provided meaningful decarbonization. The most damning evidence came from an independent report commissioned by the influential Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) finding that “various types of carbon credits are ineffective in delivering their intended mitigation outcomes.” Even taken at face value, the IPCC reports that agriculture, forestry, and land based based carbon credits created emission offsets or reductions of 7.9Gt of carbon dioxide equivalents over the 10 year period of 2007-2018. During the same time period, the world produced 412Gt of carbon dioxide.

Yet, the yearning for them has featured prominently over the decades of international climate policy. It is essential to direct all this money somewhere more beneficial for decarbonization.

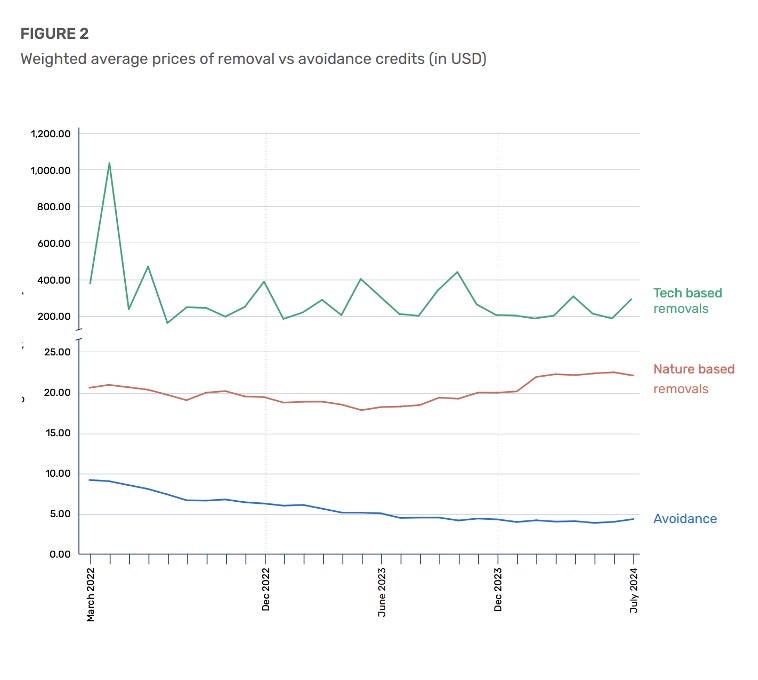

At least some proponents of carbon markets argue that the first principle for carbon credits should be that they are issued only for actual removal of carbon from the atmosphere. Doing so reduces the opportunity for fraudulent schemes based on carbon avoidances—that is carbon that would have otherwise gone into the atmosphere supposedly absent the scheme. The World Bank reports that carbon credits from technological removal fetch a far higher price because they are of a far higher quality.

Tax credits for carbon capture and utilization have been implemented under both Democratic and Republican presidents, reflecting a history of bipartisan support for the technologies that lean on existing experience, technology, and successes, and advance new technologies. The Biden administration has provided significant financial support for development of various commercial-scale direct carbon capture projects. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) announced the establishment of a Carbon Dioxide Removal Consortium to develop measurements and standards for carbon dioxide removal with an initial focus on forests and direct air capture. To boot, the IPCC is in the process of developing a special report on carbon capture removal expected in 2027.

Frankly, carbon accounting fraud is a sideshow that reflects the interests of wealthy, market savvy people. Truly fraudulent is the idea that forest dependent, rural families living in mud huts is a good place to initiate an unregulated financial market with aspirations of decarbonizing a global economy that marginalizes the interests of these very same families.