Lie to Me

How Climate Change Hyperbole Makes America’s Insurance Problems Worse

By Jessica Weinkle

In recent years, alarm has grown over homeowners’ increasing insurance premiums and the difficulties they face securing necessary coverage for catastrophe risks, such as wildfires and hurricanes.

According to one estimate, average home insurance rates have increased by almost 20% between 2021 and 2023. According to another, within the last 5 years, homeowners’ insurance premiums have increased by 34%.

Headlines herald an insurance crisis. Insurers cite unprofitability upon withdrawing from hurricane and wildfire-prone states. In early July, State Farm in California requested a 50% rate hike after it had canceled 72,000 homeowners policies.

This whole insurance mess is commonly credited to climate change; climate change has made our weather extremes more frequent and intense causing increasing disaster losses, the story goes, and now we must pay the price through insurance rate hikes for not decarbonizing rapidly enough.

But this view distorts scientific knowledge and marks a tremendous disservice to the American public, which is struggling with insurance premiums for less coverage while facing the fatalistic spell of climatism.

Meanwhile, the NSF and NOAA have agreed to subsidize the reinsurance industry’s climate risk modeling needs. Reinsurance Association of America, the reinsurance industry's top interest group, with no limit on lobbying, will work with NOAA to “develop new risk-related products of significant value to RAA, the insurance industry and other stakeholders.” It’s not clear that what is of value to industry advocates is of value to the public interest.

We must clear the confusion created by climate change advocacy to gain a clearer view of the insurance challenges America is facing.

Disasters and Climate Change

While all forms of media, policymaker rhetoric, and classroom chatter is filled with strong assertions about how climate change is apparent in more frequent and severe weather extremes and ever increasing losses- there is a dearth of evidence to support the claim. While climate change is real and important, the dominating cause of increasing losses from weather extremes is exposure growth and inflation.

Note the subtle shift from attention grabbing to substance, from future to present, in Swiss Re’s 2023 finding on the state of the reinsurance industry:

Insured losses exceeding USD 100bn [per year] globally are likely here to stay, and will grow further fuelled by economic value growth, urbanisation, and climate change.

A short while later in the report, Swiss Re states that:

The magnitude of climate change impact on the growth of natural catastrophes in frequency and severity is not explicitly quantifiable yet, whereas property value growth and urbanisation are reasonably understood risk drivers.

The first statement looks to the future. The second statement explains our current situation.

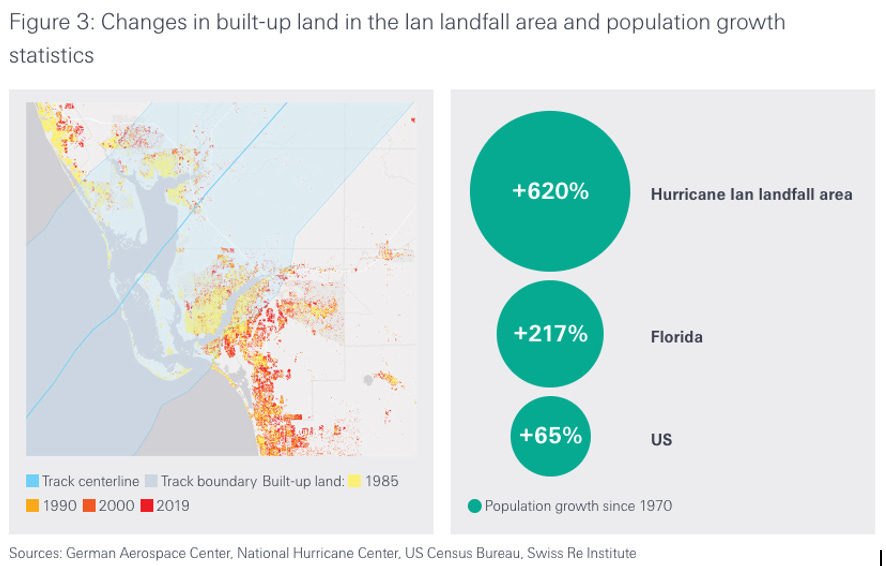

Swiss Re illustrated the importance of urbanisation as the cause of loss by using Hurricane Ian, which struck Florida in 2022 as an example. It caused so much loss precisely because the areas it hit had experienced tremendous population growth in the years before.

Other extreme weather events where losses are largely due to population growth, increasing wealth, and inflation include severe convective storms, hurricanes, floods, and wildfires.

The usefulness of climate change in insurance politics

Risk is a funny thing.

The classic adage is, “Danger is real, but risk is socially constructed.” This means that planes fall out of the sky, hurricanes make landfall, nations war. But how we think about these things or how we measure the probability of any of these things depends on our values and priorities.

Last year, a research study partially funded by a reinsurance company set out to find a climate change signal in hurricane data. The researchers concluded that discerning changes in hurricane characteristics presents epistemic uncertainty. The explain that decisions about how to frame the data depends on what you are trying to do:

How one views the situation must ultimately be based on one's particular application and the consequences of changing TC frequency…In terms of risk, it is useful to note that while in everyday language risk is associated with danger, harm or negative consequences, in business and finance risk simply refers to the uncertainty of potential outcomes, can be positive or negative. From that perspective the epistemic uncertainty present in [hurricane] climate change signal can only serve to increase risk.

Not everyone benefits equally from embracing epistemic uncertainty, however.

If you are a homeowner, you might argue that since it’s unclear whether any change truly exists or what changes there may be in the future, epistemic uncertainty should not be factored into insurance costs because it presents unaffordability risks.

If you are an (re)insurer, you might argue that you are better off safe than sorry, and you want to include it in your pricing- and besides, the ability to mix and match different scientific assumptions provides a competitive edge in the marketplace.

If you are an investor in an insurance linked security you might argue that using climate change assumptions to increase hurricane risk presents a convenient way to reduce the likelihood you lose your investment, while increasing the interest you can demand.

Epistemic uncertainty about climate change appears to have more potential value for industry interests than for public interests.

However, the constant stream of climate change and extreme weather hyperbolic messaging shapes expectation for the use of epistemic uncertainty in insurance pricing. In one survey of homeowners, 40% blamed corporate greed for rising insurance premiums. Another 86% noted that they thought companies were using inflation as an excuse, and 66% agreed that climate change was a contributing factor.

Note how climate change expectations relieves the industry of scrutiny for pricing epistemic uncertainty and relieves regulators of responsibility for questioning it.

Other real life things

Leading causes in rising insurance prices of late is loss experience, fluctuating market dynamics, investment opportunities, and cost of capital. This means that as the market conditions change—say, there is a global pandemic that results in a stock market crash followed by rapid inflation and interest rate hikes—the insurance industry is also influenced by that.

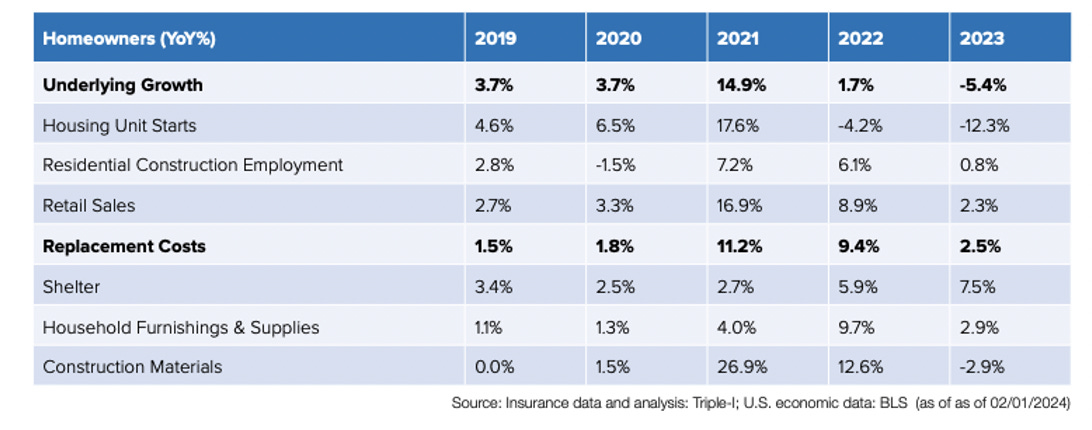

If you’ve tried to build anything in recent years, you know that material costs have increased substantially. One analysis estimated that replacement costs related to homeowners insurance soared 55% between 2020 and 2022. Another analysis showed construction material costs increased nearly 30% in 2021 alone. This all leads to insurance pricing increases.

In addition, the industry has lamented skyrocketing social inflation, a term used to refer to real or perceived overly aggressive “billboard attorneys” encouraging clients to sue their insurer coupled with generous jury awards.

Further, there have been meaningful loss events. From Hurricane Wilma in 2005 to Hurricane Harvey in 2017, there was a notable drought of major hurricane landfalls in the United States. This matters because, in the United States, hurricanes are the most costly weather events for the global insurance industry. When there aren’t major losses from U.S. hurricanes things are trending positively. When they do occur, it can have significant consequences for pricing dynamics.

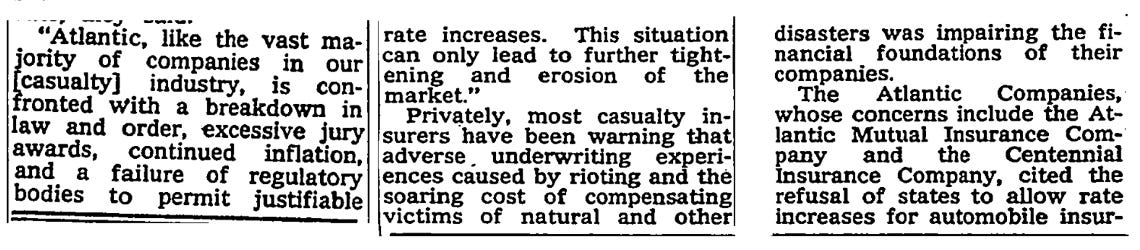

Interestingly, all of these factors are reoccurring reasons for volatility in insurance pricing since homeowners began having problems with its affordability. The clip below is from a 1968 New York Times article explaining why insurance costs were increasing. It was in this very same year that several state and federal governments developed public insurance programs for catastrophic risk.

We need economic and infrastructure policy not climate change advocacy

Florida regulators now permit the use of climate change assumptions in estimating hurricane risk for insurance ratemaking in the state, boosting views of risk. Many other hurricane prone states use Florida’s approved models for ratemaking. This means whether there is a detectable change in hurricane frequency or severity attributed to climate change (there is not), people are being charged for it in their homeowner’s insurance.

Industry reporting suggests this is going on across the sector. At the end of the record breaking lull in major category landfalling hurricanes, reinsurer Guy Carpenter announced in 2019:

Ominously, the specter of climate change points to a future that will see only more frequent and severe weather events. Risk models will need to be recalibrated to accommodate this.

This month, an industry news outlet announced that insurers and reinsurers are recalibrating their risk models in response to extreme weather losses.

Elsewhere, mortgage bond investors use climate change scenarios to argue that insurance mispricing has caused an asset bubble in the U.S. residential real estate market.

It might seem trivial if industry and climate change advocates are making the bitter pill of higher insurance costs easier to swallow for homeowners by labeling it green and encouraging emissions reductions. However, this tactic is consequential for both the economy and policy making (and science, but that’s a different conversation).

America’s $13 trillion residential mortgage market hinges on the availability of affordable homeowner’s insurance, which has come to increasingly rely on capital market investors to help carry peak risks. This is a fickle group with different priorities than most American homeowners want to stay in their kids’ school district. The precariousness of the relationship between mortgages and affordable insurance is not even remotely caused by climate change. Though, it may be exacerbated by a fervor for climate change, epistemic uncertainty, and misleading headlines.

That said, devastating loss potential is quite real; hurricanes in Miami do happen and lots of nightmare scenarios can be imagined for back to back catastrophic events. There are trade-offs gambling with insurer solvency in favor of mortgage market stability. Those trade-offs should be made plain without muddling them with mischaracterizations of climate science.

Prices reflect market dynamics but how the market conceptualizes risk may conflict with broader public goals and concerns. If industry is using epistemic uncertainty to meet their own business goals, it’s reasonable to question if that’s really an appropriate use of researchers’ conjecture. The financial industry's interest in climate change science and the potential corresponding pressure this interest may be placing to create risk products by expanding epistemic uncertainty should be scrutinized by both scientists and the public.

Policymakers need to encourage innovation in public accessible risk management. Disaster insurance can be “reimagined.” Public risk pools are no longer an aberration but a useful tool for engaging and incentivizing insurance markets.

We can build more innovatively and reduce regulatory and procedural barriers to encourage industry investment in public infrastructure and risk mitigation.

Insurance premiums that rise faster than household incomes reduce affordability of insurance. This issue is intensified by the far broader problem of stagnating incomes for much of the population. Thus, making headway on incomes and jobs can improve our situation with catastrophe insurance.

There are many ways to address America’s insurance problem, but it requires a radical reframing of the problem from one of climate change to one of real-world economic, infrastructure, and risk mitigation policymaking.