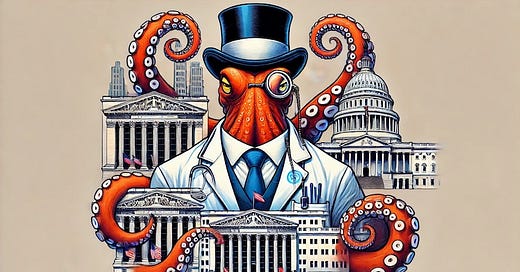

The IPCC Is the Trust We Need to Bust

“Climate Cartel” is a science policy problem

By Jessica Weinkle

In June, the U.S. House Judiciary Subcommittee on the Administrative State, Regulatory Reform, and Antitrust held a hearing on whether the investment industry had committed antitrust violations in the pursuit of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals.

The focus was less on ESG in general, however, and more on the practices of Climate Action 100+ in particular. Self described as an “investor-led initiative” to reduce emissions and produce climate-related financial disclosures, Climate Action 100+ is now under fire for behaving as a “‘climate cartel’ of left-wing environmental activists and major financial institutions” that “has colluded to force American companies to ‘decarbonize’ and reach ‘net zero.’”

The Climate Cartel, the House Judiciary alleged, has “declared War on the American way of life,” targeting disfavored American companies “that allow Americans’ to drive, fly, and eat.”

The acrimony driving the hearing would come as no surprise to critics of market-based solutions to climate, who have said all along that people would get angry if decarbonization means the end of cheap energy and modern creature comforts. Rather, accelerating decarbonization requires clear government policy and coherent regulatory regimes. Investment activity towards those stated policy goals can follow.

The investment activity set up to support the ESG ideal has made plenty of money for the firms creating ESG funds. According to commentary in the Harvard Business Review,

as passive funds have continued to grow in popularity, asset management revenues as a percentage of [assets under management] have fallen by 4.6 basis points over the past five years. ESG funds typically charge fees 40 percent higher than traditional funds making them a timely answer to asset management margin compression.

Yet the environmental benefit from ESG is unclear. Channeling investment away from high emission companies to low emission companies is counterproductive for decreasing emissions. The low emitting companies have little to change. The high emitting companies need the investment to reduce their emissions. To make ends meet in the near term, high emitting companies may double down on their high emitting ways.

In the context of high emission societal essentials—like energy and fertilizer—rapidly contracting the oil and gas companies does not itself make low carbon alternatives appear. What it does do is force people to source these essentials from elsewhere, at a higher cost, and with the same or worse environmental impacts.

That lackluster performance is backed up by Climate Action 100+’s own reporting, which shows that its real accomplishment has been producing more reporting and documentation, not reducing emissions.

Along the same lines, the compliance costs associated with the new SEC climate risk disclosure rule (which is on pause while in legal limbo) is projected at between $6–$25 billion, depending on who is counting.

Let’s bring it back to the hearing in the House. Republican legislators were focused on demonstrating collusion among Climate Action 100+ members and agreement to restrain trade. Key testimony came from Mindy Lubber, CEO and president of the sustainable finance nonprofit, Ceres. Lubber is also a member of the steering committee for Climate Action 100+, which Ceres helped found and manage.

Lubber was adamant that Climate Action 100+ members acted on their own to do what is best for their own companies and they sought to accelerate company emission reductions “if there is a financial risk to those emission reductions.” Responses to legislators’ questions consistently focused on the analytical commitments of members. For instance, in an exchange with Representative Dan Bishop (R, NC):

Bishop: Does signing [onto Climate Action 100+] indicate agreement?

Lubber: No. It indicates every investor will look at the financial implications of climate risk.

Bishop: So they are signing to say, they are not agreeing to anything…

Lubber: They are agreeing to address and look at the financial risks and implication of climate change

In response to later questions Lubber states:

“We work with a number of investors who look for information, background facts on the financial implications of climate change…”

“We are sharing information about the financial risk of climate…”

“We do an analysis of financial risks of climate change…”

Following Lubber’s explanation, Climate Action 100+ commits investors to adopt “distinct analytical methodologies” and climate risk metrics. The underpinning of coordinated behavior among investors is their shared technical assumptions and methods about climate financial risk.

This opens a window onto the ecosystem of climate science used in these analytical endeavors; an ecosystem long critiqued by nonconformist scientists for being too homogeneous and non-competitive. The result is stifled innovation in research and in the development of technologies and pragmatic methods of improving resilience and sustainability.

The problem of the real or appearance of collusion among investors guided by climate analytics is a problem of stagnant science and technology policy in the climate, earth, and sustainability sciences.

Climate’s knowledge monopoly

There are pervasive professional and institutional pressures that keep climate change science self serving and unresponsive to societal needs and political complexity.

The influence of the IPCC on the production and use of climate change science can not be understated. This is because, as described in 2011 by economist Richard Tol, the IPCC holds a natural monopoly on science advice for climate change policy. It’s not that there are no alternative views available; it’s that the dominance of the IPCC hinders the competitiveness of these views.

Since 2011, the development of Future Earth as a mechanism for organizing global environmental change science further reinforced the IPCC’s control of climate policy guidance. The organizations founding the Future Earth project favor earth system modeling because the institutions that they represent are resistant to change. It is a self-serving process.

Like other monopolies, as the IPCC acts in its own best interest, quality declines, and innovation is slow. Although the IPCC offers a free service, its monopoly “brand” power has allowed it to capture areas of research and policymaking beyond its core mandate. This is particularly so in the area of scenario development. Tol explains,

While the IPCC was set-up to assess the research on climate change, it has also engaged in primary research on scenario building, standard setting, monitoring, and research funding. The IPCC is not particularly well-suited for these activities, and one may argue that it would have failed in these tasks had it not been for a cross-subsidy in kind (goodwill, reputation, trust).

The IPCC has moved from a mechanism to report on the state of knowledge about climate change to a standard setting mechanism. Tol writes,

The IPCC scenarios are more widely used than any of the alternatives. This is true for the climatological literature, the impact literature, and the emission reduction literature. This is partly because standardization of scenarios enables comparison of results and partly because the IPCC reports are more likely to refer to papers that use IPCC scenarios. A rational researcher would therefore use the dominant scenarios—that is, those of the IPCC. The scenarios run with the large-scale climate models are coordinated with the IPCC. Therefore, the IPCC has used its monopoly position in the market for assessment to establish a dominant position in the market for scenarios.

In my previous post, I pointed out that those making decisions about scenarios for use in IPCC reporting—and thus the broader research community—are also involved in designing scenarios for use in the financial industry.

In effect, standard setters have industry interests and they work with monopoly power.

The IPCC is also the organization that provided legitimacy to the 1.5oC temperature target that was codified in the Paris Agreement. That target was the result of political negotiation (not scientific assessment). Its political and technological feasibility is broadly questioned if not flatly rejected by most. Yet, the IPCC’s brand gave it credibility, and it is now used to demand massive investment towards meeting the goal.

The IPCC is also the standard setter for emissions accounting through its production of the GWP-100 metric which is then used in emissions trading and derivatives. This is not the IPCC’s doing, but the IPCC has not refused the responsibility either.

Finally, the influence of the IPCC has shaped the development trajectory of climate modeling toward advancing high resolution models. These models are of interest to the earth science community and financial firms projecting the consequences of climate change. But it is not the kind of modeling that is necessarily the most useful for understanding uncertainty or advantageous for policymaking and community adaptation efforts.

More research is needed, but not that research

A court may yet decide if Climate Action 100+ has violated antitrust law. However, the phenomenon legislators are examining has much deeper roots. Busting an ESG trust will not result in stimulating more competitive and innovative activity because of the knowledge monopoly a step down the line. The trust that needs to be broken up is the stranglehold on knowledge held by the IPCC and vested scientists.

This is good news because it is a lot easier to encourage new areas of research and innovation than it is to win antitrust suits. Development of new research agendas also serve to open inquiry and diversify viewpoints within knowledge institutions like universities and research organizations. Government agencies can signal demand for new types of knowledge which legitimizes and elevates the prestige of researchers working on non-dominant narrative areas of study.

Well thought out research initiatives developed by the NSF, for instance, can advance understanding about scenario feasibility, legitimizing researchers in challenging the dominant perspectives held at the IPCC. Encouraging advancement of forms of modeling other than high(er) resolution climate models can encourage the development of modeling products better suited for resource strapped community adaptation decision making.

Universities and departments can also evolve the reward structure for their researchers. Traditionally, the academic profession places much weight on peer review publishing in elite research outlets. But the peer review process leaves much to be wanting and the most elite journals have become media powerhouses skewing their incentives towards promulgating dominant dramatic narratives. Universities can give more weight to their faculty contributions to high quality research disseminated through more contemporary channels like non-university based research groups. When faculty are rewarded for contributions to creating diversity in thought in public and policy spaces it encourages researchers to explore new idea areas.

Shaking up the institutional black box of climate science can empower communities grappling with resilience planning, insurance regulators wading through industry risk analytics, and the development of more insightful state and national climate science advice that is not just a regurgitation of the monopolistic IPCC.