Well, there went summer… Here are a few of things that I should have posted a long the way.

State Science Advisors are Important and North Carolina’s can do better

State science advisors are valued because they are: ‘our experts from our institutions’, to paraphrase a shared sentiment from many corners. However, what goes on in state science advice receives considerably less attention than what goes on at the national level.

State science advisory mechanisms developed primarily in the 1960s to take advantage of distributions in federal research and development expenditures, explained Harvey M. Sapolsky in 1968. Forty years later, a recap of a National Academies of Science convocation on State Science and Technology Policy Advice reflected that

As the federal government becomes increasingly constrained because of other commitments and political disputes, states and localities have unprecedented opportunities to use science and technology in productive ways.

The recap cited scientists seeking to demonstrate that science and technology are “actually organizing principles for government and policy” and improve scientists’ skills in “influencing” public policy.

In the United States, where much federal legislation is carried out with a a lot of leeway at state and local levels, state science advisers engage with policymakers in ways that are more directly meaningful to communities than what happens at the federal level.

Consider, for instance, in the United States much pandemic response occurred at the state level engaging- to more or less extents- state advisers. This wasn’t just because national level science advice in disarray. It occurred because the federal government has limited powers over the states, as it so happens, particularly in situations of public health.

As a result, what goes on in state science advice matters a great deal. If state science advisors have symbolic capital by being ‘one of us’ than it is important that they honor that privilege by acting in ways that encourage trust in the policymaking process.

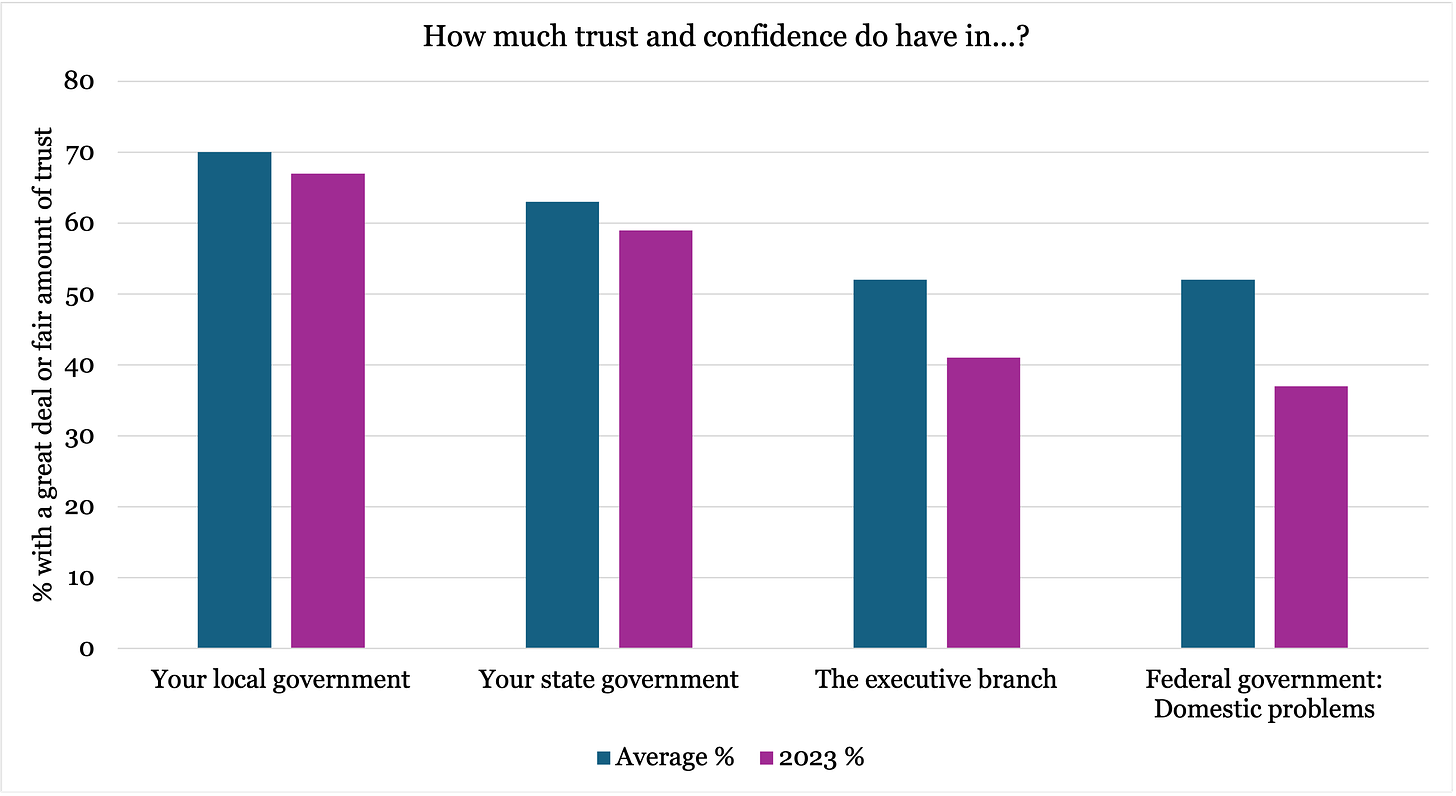

Even though trust is government is down in general, Americans trust state and local government more than federal government. So, science advisers working at state and local levels are in an important place to foster trust in policymaking. But, equally so, they can undermind trust in these places as well.

From this context, state science advice that does nothing but regurgitate federal science advice provides little. It provides state policymakers without any additional expertise, squanders the symbolic capital of ‘being one of us,’ and extends the distrust in federal government to the local level.

I say this in reference to the draft report on Sea Level Rise produced by the North Carolina Coastal Resources Commission Science Panel. The bulk of the report was a cut and paste job from the executive summary of the federal level sea level rise report released in 2022.

I submitted comments during the public comment period and focused on two issues part of charge to the Science Panel

The Draft Report does not address “new and significant scientific literature and studies” about emission scenarios underpinning SLR scenarios.

The Science Panel reports a main finding of projected SLR of 2-7 feet by 2100. This statement is misleading because it includes the use of implausible and extreme high emission scenarios.

The Science Panel does not address the “range of implications of sea level rise” by lacking reporting on the role of adaptation and providing a pragmatic approach for understanding SLR scenarios.

There is substantial potential for adaptation measures to reduce- almost completely- the economic impacts of sea level rise.

My complete comments are available below.

I note two things.

First, the Science Panel has been consumed with (unpaid) work in developing a new method for identifying the boundaries of hazardous inlets. Yet the problem of better coastal management has already been identified as one of policy implementation and communication. It’s not a science problem- it’s a political problem. Policymakers have to do the hard work of politics and decision making.

Second, if the Science Panel was unaware of controversies in emission scenarios and SLR estimates than they did not have the requisite expertise to do the report. That’s okay; no one is an expert in everything. If they were aware and chose not to engage the issue then something else is going on.

They should explain their choices.

Science and scientific publishing has a problem

Climate science is not the only politicized practice in town. Fisheries has it too.

A recent paper by Cochrane and colleagues documents the impact that several controversial papers has had on policymaking in fisheries management and marine protected areas. The authors main point is that science is a process; knowledge does not accumulate in a pool like a dripping faucet. Healthy scientific debate and not so healthy methodological sleights of hand are too frequently lost to the fast pace of headlines stirred by the media powerhouses of high impact journals.

The scientific method relies on a process where differences and diverse views are debated over time before a contentious matter is considered to have been settled. All scientific information that is considered and used to influence policy development and management should have been through such a process before it can be considered a part of best available scientific evidence. However, in the general field of environmental science, and probably some other disciplines too, this process has frequently been disrupted by the view that a paper that has been published in the primary literature is thereby sufficiently reliable to influence long-term policies, without needing or allowing for adequate debate and opportunities for checking and correction when required. The examples presented here were directed at high profile topics in the arena of fisheries management and marine conservation, and their findings have also typically been promoted by media campaigns. Within that looser approach to what constitutes reliable scientific information, they were surely intended to influence policy debate and the making of potentially far-reaching decisions.

Even retracted papers can live on in perpetuity.

The authors place most of the responsibility for the state of affairs on the journals themselves, difficulties in the peer review process, and pressure on academic researchers to publish.

The editors and reviewers are serving the publishers of the journal. A primary motivation for publishers is financial: many are commercial profit-driven companies. While these publishers might contribute resources and sincere commitments to corporate social governance initiatives, their business model is commercial, which further incentivises the publication of high impact articles with high publicity value. Nevertheless, that drive should not jeopardize the scientific merit of the papers. Scientific journals should, in principle, take responsibility and be held accountable for the quality of the papers they publish and, in instances of high impact papers, the consequences of errors and misleading information.

Cochrane and colleagues also point to growing problems in authors’ and reviewers’ non-financial conflicts of interests- something they refer to as “emotional” conflicts.

COI can affect the judgement of reviewers and editors as well as that of authors, as seen in some of the examples provided here. COI guidelines for all in the process need to encompass all likely cases of conflicts from financial to emotional, and to be well enforced. Particular care is required in choice of handling editors, who should not edit any papers where they themselves have an advocacy position.

Freedom Research Podcast

The folks at

were ever so kind in having me on the show. We spoke about a range of things from climate anxiety in young people (an issue in eastern Europe, too), and disasters and climate change.