Scrutinize insurance ratemaking

Climate change narratives about the public's insurance problems conflates climate change advocacy with a century's worth of insurance politics

I recently returned from a wonderful trip to California where I visited with family and friends, and made some new acquaintances. On the forefront of many people’s minds is wildfire and recent volatility in the state’s insurance market caused by big name insurers refusing to write new policies.

The insurance business is technical and complicated. These complexities are main culprits for the public experience with insurance. For one thing, insurance is really only one aspect of the business. Behind the scenes there is also ‘the float,’ to which Warren Buffet has history of referencing as one of Berkshire Hathway’s greatest successes.

The consumer advocacy group, United Policyholders, does good work in bringing the complexities of the insurance business into public discussion.

In their recent blog post, UP directs readers to a summary about a 2012 blog post I wrote while a grad student about how changes in scientific assumptions embedded within catastrophe models creates tremendous political and economic disruption in society. The conflation of climate change advocacy in science with catastrophe insurance politics in Florida was the focus of my dissertation.

What is often passed off as climate change impacts is rather, modeled risk using climate change assumptions. The difference between those two things reflects some of the politics of detection and attribution.

The dominant narrative neglects history

As it typically does, popular headlines took the situation in California as a harbinger of climate change and a future of uninsurability.

The functional politics of this discourse is to mobilize climate change advocacy behind the position that insurance rates should increase, and implicitly, that ratemaking practices should be free from too much public scrutiny.

For the record, I have no idea what insurance rates should be. But it is problematic that such an important aspect of our economic lives- insurance- is so often engulfed by climate change advocacy.

Insurance, and problems with insurance, is part of the nation’s (US) economic history particularly in situating housing as foundational economic policy.

For an excellent read on debates about the role of the NFIP as a housing policy and its multidimensional value to American families see Underwater by Rebecca Elliott.

…and it’s a long history

Early debate about insurance rate regulation stems from grassroots disgruntlement with fire insurance costs around the time of the Progressive Era. People were miffed that they both needed insurance for economic activity and that insurance was too costly.

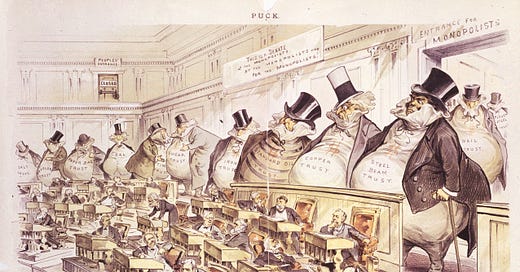

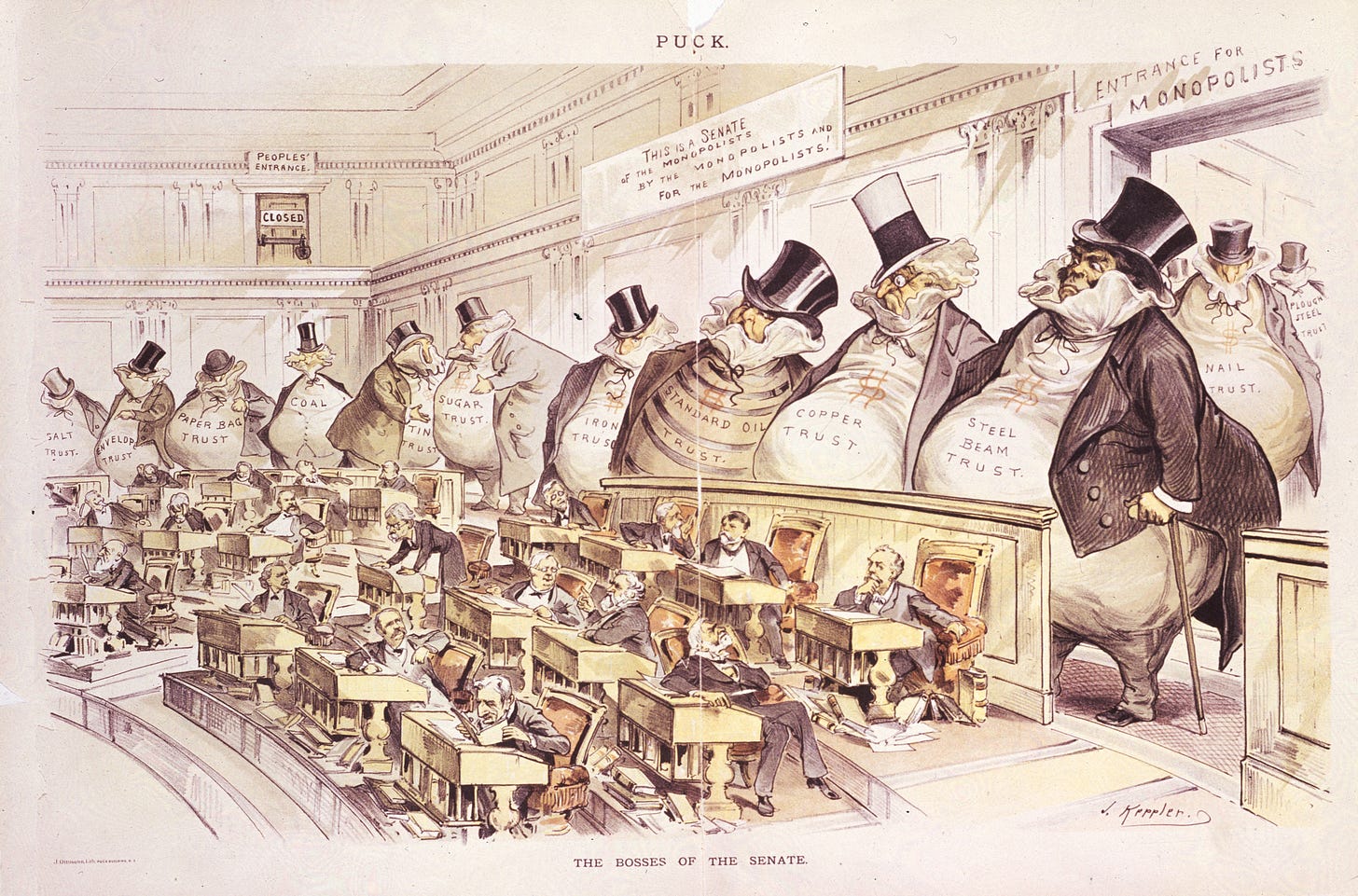

Fire insurance had been “exceptionally fertile ground for interfirm association” leading to fierce competition that drove insurance costs too low and then price fixing driving rates higher. The volatility drove political opposition to the “insurance trust.”

However, the business of insurance remained exempt from Federal antitrust legislation like the Sherman Act (1890) at least since the Supreme Court decided in 1869 that insurance is not commerce and therefore, not subject to the Commerce Clause of the Constitution.

The view that insurance deserves a close regulatory eye was upheld by a 1914 Supreme Court case that decided insurance is “affected with a public interest.” In short, the court found that insurance is so fundamental to broader economic activity as to be “essentially different from ordinary commercial transactions, and … is of the greatest public concern.”

So, insurance ratemaking is subject to state regulation. Sometimes, and increasingly often in cover for wind, flood and now fire, such regulation keeps rates lower than insurers prefer in an effort to ameliorate risk to other large scale economic endeavors.

As the US entered its 5th year of WWII, the Supreme Court heard a case about price fixing among an association of nearly 200 fire insurance companies, the South-Eastern Underwriters Association,

The conspirators not only fixed premium rates and agents' commissions, but employed boycotts together with other types of coercion and intimidation to force non-member insurance companies into the conspiracies, and to compel persons who needed insurance to buy only from S.E.U.A. members on S.E.U.A. terms.

At which point, the Supreme Court overturned its earlier ruling finding that yes indeed insurance is subject to the Commerce Clause and Federal antitrust legislation.

In response, Congress passed the McCarran-Ferguson Act providing limited exemption for insurers from Federal antitrust legislation and ensuring that states would maintain authority over insurance regulation.

The insurance industry is a fierce defender of McCarran-Ferguson. If III is any indicator of the leading argument, then the industry’s primary concern regards how Federal antitrust legislation might impact data sharing.

(Interestingly, just days before former President Trump left office he signed into law the Competitive Health Insurance Reform Act of 2020 limiting McCarran-Ferguson protections for health insurance though continues to protect data from antitrust legislation. The act passed both chambers unanimously.)

Little houses made of ticky tacky

In 1950, the insurance industry introduced the homeowners policy, which became requisite for any mortgage. Homeowners packaged multiple perils into one discounted premium (relevant here, it packaged together fire and wind which had been separate lines- fire and casualty). The discount was key to selling the policy,

if a multiple line policy in the individual homeowners field was to have any success, it had to have features or benefits which were sufficient to create a demand, or, perhaps more realistically stated, it had to be a policy which could be sold.

The boom in homeownership during the 50’s was accompanied by wild success with the homeowners policy which was accompanied by further discounting of the premium. Writing in the 1960s, an actuarial history of the policy notes that,

Homeowners is here to stay but, as with any line of insurance, there are and will be problems. Under the pressures of competition, premiums have been reduced and there is no indication of a situation developing whereby premiums will become excessive or have any "fat." At the same time there is no indication that losing money has become fashionable and rates will inevitably go up (or expenses will be cut or both) if there are clear indications of unfavorable experience.

Unfavorable experiences began to be felt in earnest with several hurricane destructive landfalls in the 1960s, particular “Billion Dollar Betsy.”

All sorts of residual markets were developed to help stabilize homeownership as an economic policy while insurers raised rates and pulled back from coastal areas. FAIR plans, Beach plans, and the NFIP were developed with the passage of the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968.

There is a public interest in examining risk model assumptions

Things became a lot more complicated with the rise of computer modeling in finance in the 1970s, and then in the 1990s in insurance.

Modeling different risk creates important questions about whose future we ought to manage and the role of insurance in making these decisions. Scholars in the social studies of insurance refer to this as, “insurantial imaginaries.” According to Booth et al,

the term ‘insurantial imaginaries’ describes the shared structures of comprehension and action that establishes the social value of insurance and its practical influence.

But the history of insurance politics is all still there, as is the business complexity, the float, and our foundational economic policies.

The assumptions insurers use are not easily accessible. There is lots of secret sauce.

But the assumptions become a lot more accessible when the invisible hand waves away public difficulties with insurance practices using the rallying cry climate change.

What I'm taking away from this post is it's possible and probably likely that insurers are building in unrealistic worst cases into their risk models. This leads to inappropriately high insurance premiums and since the insurance industry isn't particularly transparent we are not able to effectively challenge the rates. Is that a fair assessment?