Don't hate the player, hate the game

On Patrick Brown, Science Wars, and the Academic Publishing Business

In a remarkable essay at The Free Press, Patrick Brown, a researcher at The Breakthrough Institute, gave the world a lesson on how the sausage is made in headline stirring climate change science. Start the research with the publication outlet end in mind.

The editorial practices of elite academic journals such as Nature, matter for how society understands the state of knowledge and how we relate to the world. On occasion matters arise that bring attention to the fraught activity of gatekeeping at the journal and its broader family of journals.

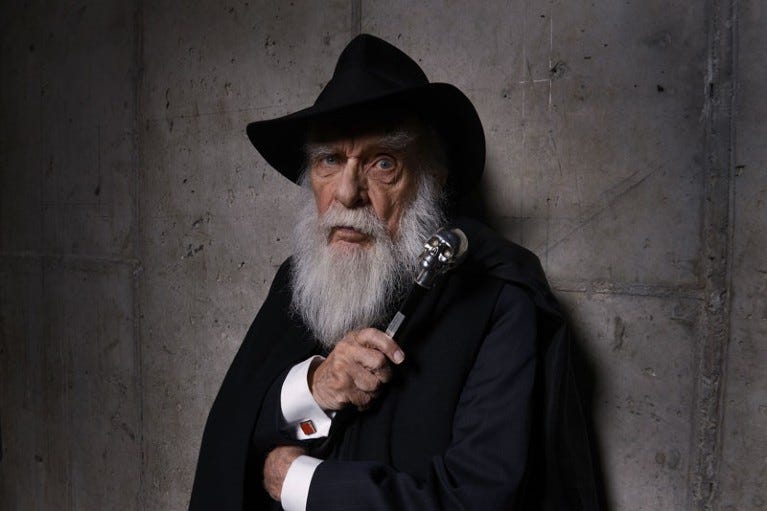

For instance, in the late 1980’s, Nature, published a research article under the condition that the journal could send investigators to the lab to review the researchers’ methods. The investigating team included the journal’s editor, a peer- reviewer with a negative opinion of the work, and “The Amazing Randi,” an illusionist leader of the “skeptical movement.”

Finding the lab’s methods questionable, Nature issued a report refuting the researcher’s findings. Reflecting on the controversy one scientist commented that the matter gives,

confirmation of what I have always suspected…Papers for publication in Nature are refereed by the Editor, a magician and his rabbit.

Far more recently, Nature’s editorial process has been shown to be malleable to external pressure. FOIA investigation into policymaker communications about the potential lab origins of COVID-19, reveal serious problems in authors misrepresenting the state of knowledge and pressure from political interests on the Editor in Chief, Magdalena Skipper.

These examples are egregious diversions from ethical publication practices. They also make plain the social underpinnings of knowledge production.

The 1990’s Science Wars was a highbrow conflict between positivists and relativists. Positivists working from the lens of an objective truth obtainable stepwise through the scientific method. Relativists worked from the lens that people make meaning of things including science through their values, culture, worldview, and relationships.

One of the biggest points of contention was to what extent knowledge is a product of the social forces on the people conducting research. The implication then as now is that scientific authority has limits. Science neither marches linearly towards absolute truth, nor can it resolve social value disputes.

People do science was an important takeaway.

The debate tended to navel gaze: are facts real? The more practically minded argued that it matters little whether or not an atom is real or a social construct, or both. To the extent that our understanding of atoms gives us nuclear weapons, plastics, and pharmaceuticals- they are real enough.

And in any case, those involved with science policy since WWII knew perfectly well that science was a product of social forces. The public held the pen for government funded research. Research programs were developed not by epiphany and good fortune, but by fierce direct and indirect lobbying.

The late Canadian philosopher Ian Hacking had quite enough of the science wars. He quipped, “Why ask what?” from which he argued the purpose of deconstructing the social underpinnings of science was to enable a higher consciousness and empower people to intervene in the knowledge production process to improve our lot.

Hacking illustrated particular concern for individuals in society. The ways researchers defined things- mental illness and child abuse, for example- mattered for how people understood their own lived experience. But, society could also have profound effects on how researchers understood the thing they looked to study. According to Hacking, revolt against researcher explanations of autism by families with autistic children led to a thorough scientific reconceptualization of the autism condition to more readily reflect family experience.

What follows then is the opportunity for society to shape knowledge production towards the development of socially acceptable technologies to help resolve real world problems.

The most notable intervening in the production of science however, has not been towards finding better ways forward and enlightening our personal experiences. Powerful policy advocates have descended on the research enterprise as an engine of political gain.

In 1997, marine biologist Jane Lubchenco, then president of the professional organization, American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), called on scientists for a new ‘social contract’ between science and society. While the old social contract developed post WWII promised societal benefit through technological innovation the new social contract would situate researchers as active participants in the political process.

Lubchenco moved on to an illustrious career in the revolving door between the executive branch, scientific research, and advocacy organizations. As part of the quest for scientists to communicate research to influence policy development (i.e. advocacy), she joined several other elite researcher advocacy notables (an examination of which could fill its own volume) to found the research advocacy organization, Climate Central. The express purpose of Climate Central is to put climate change research into mainstream media to mobilize policy change.

Of its claims to fame, leaders at Climate Central inspired the development of weather event attribution science birthing the field as the love child of climate change advocates and media. It was designed specifically to provide fodder in environmental litigation and to sway the court of public opinion through the development of sensational media headlines. The academic and policy merits of the research is, purposefully, an afterthought.

Academic journals find themselves in this deep confluence of politics and science which is apparently not so bad for business. And to be sure, academic publishing is a lucrative business estimated to have total global revenues over $23 billion.

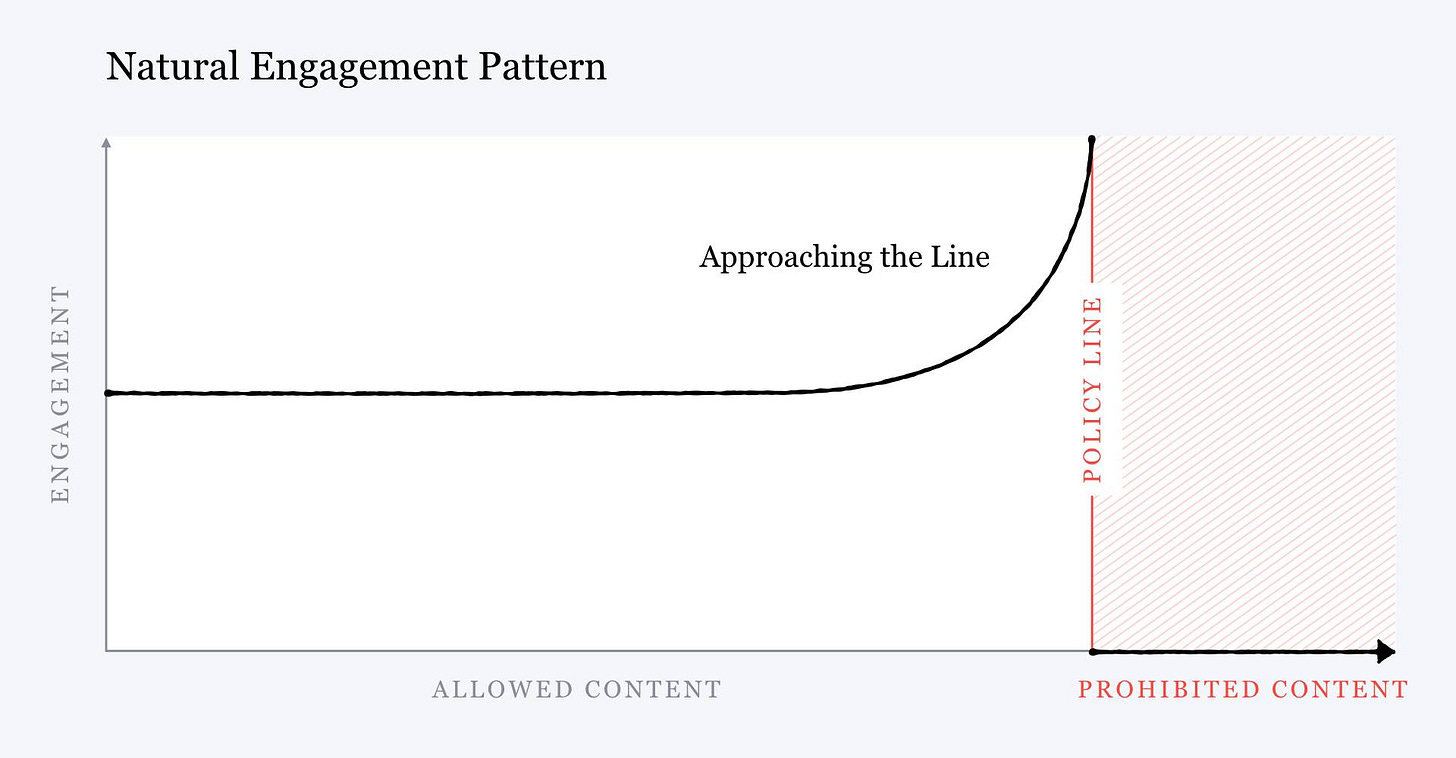

Mark Zuckerberg, King of Clicks, explains that what gets attention online is sensational information. In debating the line between allowable online content and that which is forbidden,

no matter where we draw the lines for what is allowed, as a piece of content gets close to that line, people will engage with it more on average.

And so, it should not be surprising that academic journals prioritize publication of that which grabs attention in media headlines.

In turn, as Brown argues, what gets you into prestigious journals isn’t necessarily the value of the research towards making progress in resolving social ills. What often gets you in, is how easily research findings can be turned into clickbait. That’s the business.

But let us not forget that outside of the most elite players and organizations, researchers are doing the daily grind like anyone else. They simply need to get, keep, and advance in their job all while juggling family and personal care.

Academic publishing underpins knowledge claims and are important components of systems of prestige. Publication has long mattered for academic career advancement. As universities have (for better and worse) moved increasingly to a business-like mindset, so too have researchers been pushed for more research and more prestigious research.

The business of academic publishers are now the gatekeepers of researcher career advancement.

Much of what we think about when we consider academic publishing reflects an era long gone. Academic publishing originated in the practices of ‘learned societies’ where individuals shared research findings and ideas amongst themselves within a discipline and with no expectation of making money through publication itself.

Post WWII though academic publishing became intensely commercialized. Today, the industry may also be regarded as the “‘scholarly journal branding’ market.”

In a discussion paper about the entanglement of commercial publishing, academic prestige the circulation of research, Aileen Fyfe and colleagues summarize the significance of major publishers entering the academic publishing space,

since the 1960s and 1970s, control of the measures of academic prestige – starting with the management of peer review, and extending to the development of metrics – has been silently transferred from communities of academic scholars to publishing organisations

Today’s major academic publishers are media behemoths intensely focused on turning profit. SpringerNature, the publisher of Nature, has looked to become a publicly traded company at least three times.

In a fascinating account of SpringerNature’s failed IPOs, Jaime Teixeira da Silva and Yves Fassin reflected that it “highlights the competitive nature of the commercial publishing landscape in a non-profit academic environment.”

They conclude,

These financial deliberations might be unknown to most academic researchers, who tend to select the journal they wish to publish in for reasons of journal status, reputation and ranking and might not care for the financial intricacies of the publisher or its ownership. However, business issues, such as the Springer Nature IPO, should not be ignored by academic researchers. The academic community should involve all researchers, university administrators and research funding organizations, public or private, in a larger debate to find more equitable and fairer forms of cooperation.

Meanwhile, chasing “excellence” in research is found out as simply bad for research.

Researchers trace the roots of issues in reproducibility, fraud, and homophily to rhetorics of excellence. In effect, once a practice, group, or a journal outlet becomes “excellent” any deviation from that standard is viewed as sub-par.

To wit, Myanna Lahsen and Esther Turnhout, show how the quest for excellence has rendered environmental science stale. An unwillingness to entertain change has left the whole field with no hope of actually aiding in achieving environmental sustainability,

We argue that rarely analyzed mutually reinforcing power structures, interests, needs, and norms within the institutions of global environmental change science obstruct rethinking and reform. The blockage created by these countervailing forces are shielded from scrutiny and change through retreats behind shields of neutrality and objectivity, stoked and legitimated by fears of losing scientific authority

Chasing excellence keeps everyone humdrum and producing not so interesting things that make good headlines. But it also keeps them employed and their prestige value growing.

What distinguishes academic journal publication from publication in other outlets is the use of peer reviewers. As any university student will tell you peer review distinguishes credible research from any other ol’ thing.

But this was not always so.

Until the Cold War that peer review came to mark a piece of work as scientifically legitimate. It was not until 1973, that Nature had made peer review a requirement for all the papers it published. Even still editors maintain a great deal of discretion on what was published.

Peer review is not regarded very highly by the many that have to go through it. Today, many researchers will share that peer review is simply broken. It does not mean much more than 2-4 other people looked over the work and didn’t lament any problems the editor deemed too serious.

Is peer review important? Yes. Is it what it is made out to be in the public sphere as an assurance of significance, truth, and progress? Not at all.

And this is where Patrick Brown walks into the conversation. With expertise in extreme weather attribution science and publishing in high powered journals, Brown succinctly outlined the whole racket step by step.

The worse offense, and Brown’s overarching point, is that this entire scheme from politicized science to the business of publishing does little to nothing to improve society’s ability to advance towards its publicly stated value goals.

Is his high powered published research scientifically valid, excellent, and accurate? Absolutely.

Is it helpful? Meh.

Rancor and frenzy followed his essay.

Famous climate scientists drummed up online outrage denigrating Brown and attacking his research ethics. Media outlets shifted the framing of his work painting him in the worst light possible. So much controversy erupted that Nature’s editor (still M. Skipper) appears to be considering a retracting of the paper.

Brown clearly touched a nerve. But why?

In the long ago words of TS Kuhn, Brown is threatening a scientific revolution. By articulating the structure of knowledge production the underlying belief system and motivations, by outlining a how-to, he shows how the game is played.

Brown makes it difficult to ignore the decades worth of abundant observations that mainstream climate change science is not just politicized, it is big business. And elite journals are in on it.

Time for the 'marketplace of ideas' to address this problem by starting another publication that actually values rigor, repeatability and honest peer review. With today's web-based platforms like Substack, the barrier to entry is pretty low, and the market for honest scientific papers is wildly under-served.

Within my lifetime, I saw funding at USDA intentionally transferred from a program in which research users had a role in determining topics for research to scientists determining it via research panels (supposedly better because the research was “peer reviewed”) in reality, it just transferred decision authority to scientists themselves, who wanted to be cool and publish in eminent journals, even if it never helped any particular human beings. Congress realized this and passed the Fund for Rural America which was supposed to do that.. we actually allowed a few users on research panels. This got some people upset, and at the end the head of the program was fired and we were asked to call the PIs and retract their grants. I left the agency at that time, that was one of the worst experiences of doing something painful to the PIs for no apparent reason except internal politics. Now even Congress, I think, has given up. Patrick has only exposed the tip of the iceberg. Funding of the scientists, by the scientists and for the scientists, indeed!