Can NGFS catch a crisis?

When border collies study physics

In November, NGFS released its fourth vintage of its climate scenarios for use by central banks and regulators in stress testing. In thumbing through the associated reports, I was struck by an irony in their reference to a work by Andrew (Andy) Haldane and Robert May published in Nature. Haldane and May drew lessons from the natural sciences to argue that too much complexity lends to system instability.

Haldane, then an economist of the Bank of England, was deeply critical of the hubris in using highly complex financial risk modeling to ward off systemic financial risk. He made a name for himself in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis with circulation of an essay, “The Dog and the Frisbee.” Haldane argued that complex regulations mirror complex risk models lends to system instability.

He famously opened his argument with an analogy about catching a frisbee, which is difficult and relies on an assessment of physics. But both humans and dogs catch frisbees quite regularly, and border collies perform better at the task than humans.

So what is the secret of the dog’s success? The answer, as in many other areas of complex decision-making, is simple. Or rather, it is to keep it simple. For studies have shown that the frisbee-catching dog follows the simplest of rules of thumb: run at a speed so that the angle of gaze to the frisbee remains roughly constant. Humans follow an identical rule of thumb.

Catching a crisis, like catching a frisbee, is difficult. Doing so requires the regulator to weigh a complex array of financial and psychological factors, among them innovation and risk appetite. Were an economist to write down crisis-catching as an optimal control problem, they would probably have to ask a physicist for help.

Haldane had used a crude metric to demonstrate growing complexity of banking regulations. He pointed to various Basel Accords and its growth from 30 pages in Basel I to 616 page in Basel III.

The growing complexity, according to Haldane, reflected the shaping of regulation by the developers and users of risk models namely, the regulated:

With hindsight, a regulatory rubicon had been crossed. This was not so much the use of risk models as the blurring of the distinction between commercial and regulatory risk judgements. The acceptance of banks’ own models meant the baton had been passed. The regulatory backstop had been lifted, replaced by a complex, commercial judgement. The Basel regime became, if not self-regulating, then self-calibrating.

Yesterday’s Toolbox

Using Haldane’s complexity rule of thumb NGFS shows a familiar trend:

Technical documentation for its first vintage came in at 64 pages and 14 authors, the fourth vintage boasts 241 pages and 30 authors.

NGFS illustrates palpable frustration that the messiness of global society is mucking up its efforts to model the future demonstrated by the

consequences of the war in Ukraine on energy system trajectories are contributing to an overall increase in disorderliness of the NGFS scenarios.

Should that have been the only disorder the war in Ukraine produced.

To account for global society’s non-conformity with modeler ideals, NGFS developed a new scenarios for the, “Too little, too late” narrative quadrant.

there is a risk of further delays and fragmentation in the international climate policy landscape, made more severe by the energy crisis following the war in Ukraine. A new too-little-too-late scenario Fragmented World (FW) has been added to explore such adverse developments.

NGFS encourages regulators use the new FW scenario as a baseline for banks’ climate stress tests.

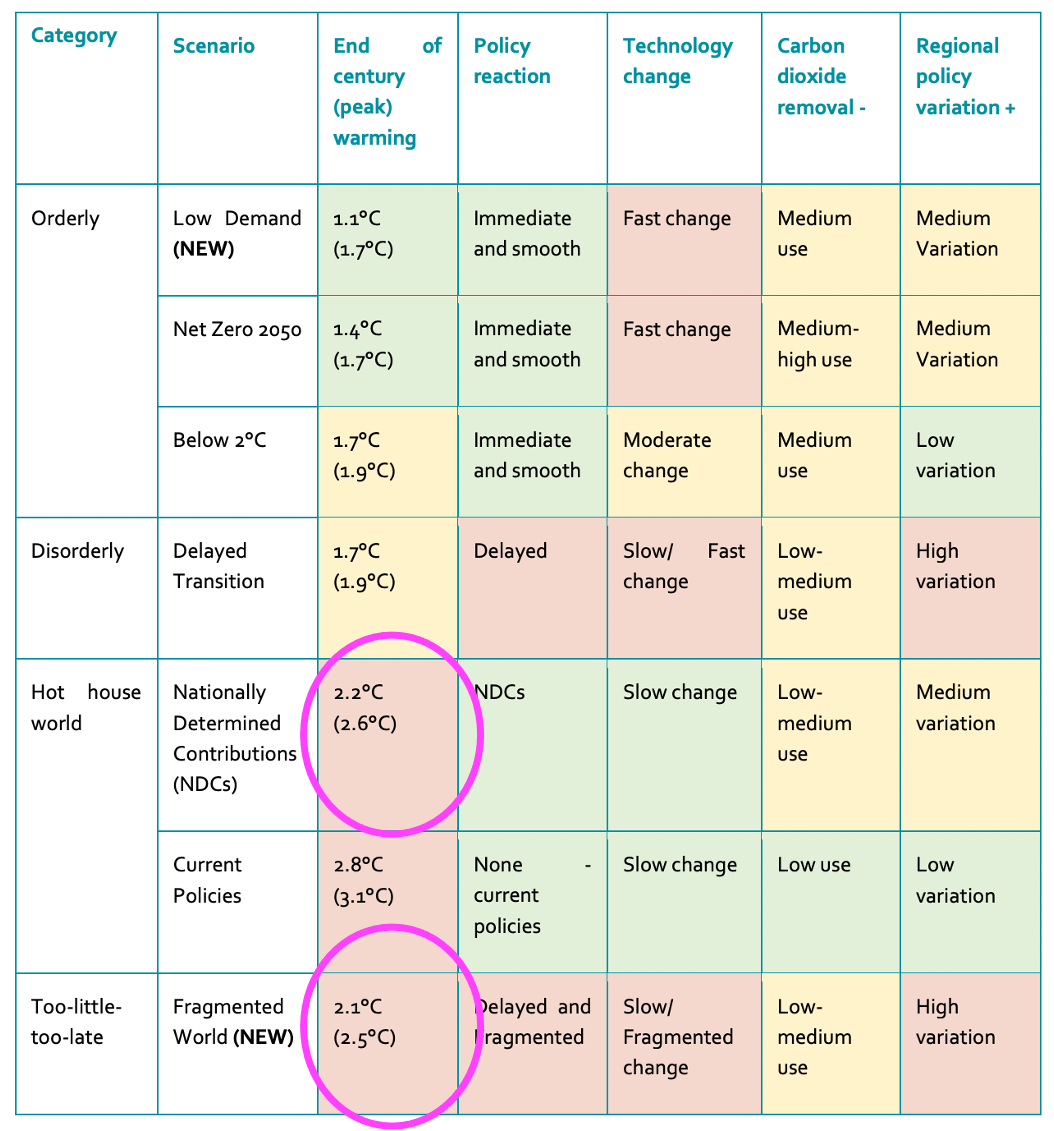

This too little, too late “Fragmented World” (FW) the messiness of global society produces (nearly) the same temperature change and physical risk as that of the Nationally Determined Contributions, as shown below.

FW has high transition risk because it has more than twice the carbon price than NDC (graph below).

V4 gives more details

NGFS v4 gives more detail to their methods behind their methods for physical risk .

A while back NGFS revealed their use of the extreme emission scenario RCP8.5 in modeling chronic physical risk and the development of their damage function. This remains. The fourth vintage decreases chronic physical risk ever so slightly. But, rest assured, they promise greater chronic risk in the future. Phew.

Where NGFS lost a bit on chronic risk, they found loads more in acute risk. Version 4 increases its measure of acute physical risk to 8% of GDP from 1.4% in Version 3.

NGFS explained that in calculating damages from acute risk it uses RCP8.5 to measure:

crop damage from drought,

heat stress, and

flood damage.

Not hurricane damage though. NGFS opted for RCP6.0 when measuring damages from hurricanes.

And what of the Current Policies scenario? The one in the middle of the two circles in the above chart and representing the highest degree of warming and physical risks.

In the fine print in the image above, NGFS writes

Current policies scenario uses damages corresponding to the 95th percentile of the temperature profile to account for tail physical risks, while other scenarios use the 50th percentile.

The upper boundary for the warming in the Current Policies scenarios is about 4.5oC by 2100, higher than the scenario’s more commonly marketed 3oC.

As a result, Current Policies achieves tremendous damages by mid-century.

NGFS rigged the temperature distribution for Current Policies even higher than would have been produced using a consistent sampling methodology.

The US Social Cost of Carbon methodology functions in a similar way.

And speaking of Social Cost of Carbon, NGFS which has in the past committed only to a shadow carbon price now speaks freely of its use of a social cost of carbon.

This module [Kalkuhl & Wenz damage function] is used to calculate an additional component in the carbon tax that captures the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC).

It would seem then that the primary difference between NDC and Current Policies scenarios is the rigging of the temperature distribution in the latter.

And because all of the scenarios are at the mercy of extreme and outdated emission scenarios, all seven of the NGFS scenarios may be collapsed down into an exploration of impacts from carbon tax rates.

Gaming the system

Overall incoherence and outdated science of NGFS scenarios introduces uncertainty into the financial system- at least as far as the scenarios are used for more than symbolic politics.

NGFS clearly does more for the job security of climate analytic consultants then for ensuring the security of the banking system as seen in recommended next steps to

Explore how the NGFS, central banks and supervisors could work with the scientific community to advance research on:

Collaborations between central banks and supervisors and academic researchers should include experts across physical climate science, catastrophe risk modelling, network risk analysis and economic and financial impact modelling…

Because those organizing international climate science for IPCC reports also create NGFS scenarios we might expect that IPCC reports and the broader climate change science community will increasingly orient towards serving the interests of the financial sector.

NGFS scenarios may also produce financial crisis by serving to legitimize this approach to measuring financial risk. And there are people who aim to short aspects of this climate model induced financial crisis- in the same way they shorted the mortgage market in 2008.

NGFS scenarios show that steep carbon prices are accompanied with steep spikes in global unemployment and inflation.

If NGFS modelers were miffed by the messy outcomes of the Ukraine invasion imagine their shock from a social response to an “orderly” international coordination of unemployment, inflation, and energy prices to ward off rigged estimates of global economic collapse.

Haldane’s conclusion rings true today,

Modern finance is complex, perhaps too complex. Regulation of modern finance is complex, almost certainly too complex. That configuration spells trouble. As you do not fight fire with fire, you do not fight complexity with complexity. Because complexity generates uncertainty, not risk, it requires a regulatory response grounded in simplicity, not complexity.

To catch a crisis by looking through the complexity of climate change science, its legacy methods, and politics onto the enormously complex system of finance is, as Haldane says, “to ask a border collie to catch a frisbee by first applying Newton’s Law of Gravity.”