Vermont’s Fossil Fuel Shakedown

The Climate Superfund Act Is Heavy on Discourse, Light on Logic

By Jessica Weinkle

Earlier this year, Vermont was the first state to enact climate change cost recovery legislation—better known as a Climate Superfund Act. Shortly thereafter New York passed similar legislation, and legislators in California, Maryland, and Massachusetts have introduced similar bills. Vermont’s legislation targets fossil fuel companies as liable for climate change. As a result, the state will send a bill to these companies to fund a portion of Vermont’s “climate change adaptation projects,” what one may otherwise refer to as infrastructure upgrades.

Rather than owning their responsibility to the public, Vermont legislators are creating laws that place responsibility on judges for getting infrastructure projects done by ensuring a revenue stream from fossil fuel companies. The real ploy here is in advancing climate litigation and creating headlines that ding industry in their sustainable corporate reporting.

Meanwhile, Vermont has significant infrastructure and economic problems unrelated to climate change. Instead of putting every spare dollar from the state’s small budget towards the mutually reinforcing goals of updating infrastructure and building an economy that supports investments, the state legislature chose to jump headlong into a technocratic smear campaign, hidden within the nuance of financial practices and accounting standards.

The situation exemplifies how climate crisis virtue signaling leads to bad politics and absurd policy.

What is a Climate Superfund? What Will it Do?

Climate superfund laws are loosely modeled on the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA). The Act enables the Environmental Protection Agency to find potentially responsible parties for environmental contamination and compel them to clean it up or pay damages. It was inspired by tragedies in the 1970s, such as Love Canal.

However, CERCLA is more widely known as the origin of the “Hazardous Substance Superfund,” a trust fund that the EPA can use to clean up contaminated sites when there is not a viable responsible party. There is a long list of sites throughout the United States in need of remediation and these are often referred to as Superfund sites. Originally, Congress funded the Superfund with taxes on crude oil and imported petroleum, certain chemicals, and corporate income. That tax expired in the 1990s, but was reinstated by the Inflation Reduction Act.

Vermont’s Climate Superfund Act aims to create a revenue stream to fund “climate change adaptation projects” defined by the legislation to include a wide breadth of activities from responding to weather related disasters to general infrastructure updates and preventative health care programs. The state of Vermont desperately needs money for infrastructure—sewers are failing, river infrastructure is crumbling, and the state cannot afford necessary improvements.

But this need, contrary to what Vermont’s climatist lawmakers report, has little to nothing to do with climate change.

Whereas CERCLA targets liability and remediation of clearly defined contaminated sites such as old landfills, mines, and manufacturing plants, Vermont’s Climate Superfund Act targets a handful of fossil fuel companies as liable for anthropogenic global warming overall. Specifically, Vermont policymakers intend to hold responsible those companies engaged in the extraction or refining of fossil fuels between January 1, 1995 and December 31, 2024. If the Vermont legislators are successful, these companies will be responsible for financial damages from the warming caused by their respective one billion metric tonnes of GHG emissions.

Vermont’s legislative diagnosis of liability for climate change mirrors the work of Richard Heede, founder of the Climate Accountability Institute. Heede’s testimony to the Vermont Judicial Committee included a slide with a list of 10 companies who emitted 1 billion metric tonnes of GHG emissions between 1995 and 2023.

The Act indicates that Vermont legislators plan to go head to head with these 10 companies. In preparation to do so, Vermont legislators allocated $600,000 for legal fees alone—half of which they intend on recovering as the oil company payments start to roll in.

Vermont’s Sewers and Rivers

Vermont’s Climate Superfund Act highlights the state’s stormwater, sewer, and flood infrastructure as examples of where Vermont is in need of climate adaptation financing to “prepare for future climate-change-driven disruptions.” But, the needed updates to Vermont’s stormwater and sewer systems and flood infrastructure is related to its urban history predating contemporary climate change concerns.

Vermont has some of the oldest infrastructure in the country. As a small rural state, Vermont lacks the typical capacities of larger state economies. In some cases, the state’s wastewater pipes date to before Abraham Lincoln was president.

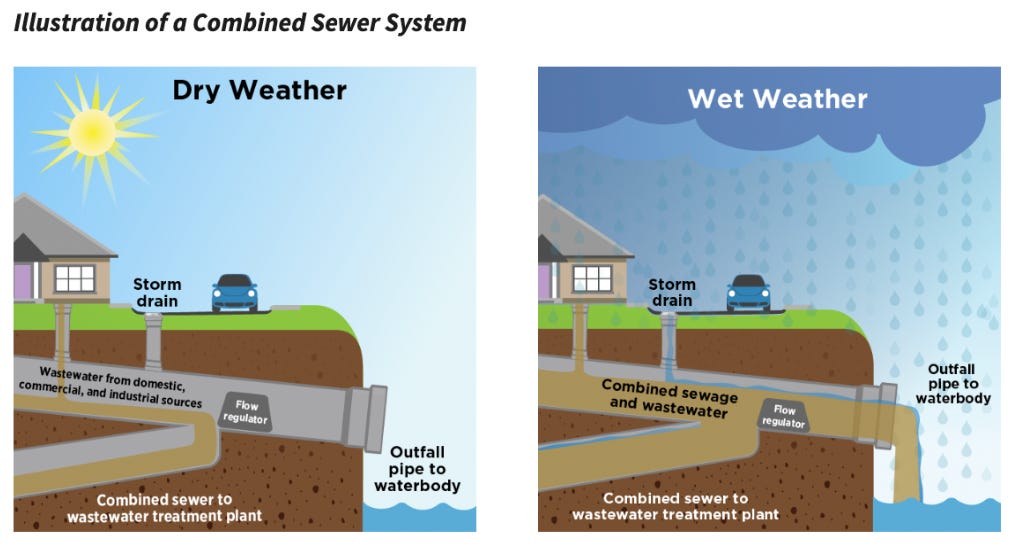

Many of Vermont’s sewers are what is called a “combined sewer system” and are among the earliest sewer systems constructed in the United States. These systems use the same pipes to carry stormwater and wastewater directly to a nearby body of water. Since the 1940s, increased regulation of discharge and especially federal funding made available through the Clean Water Act of 1972 advanced wastewater treatment across the nation and reduced water pollution.

However, installation of wastewater treatment facilities could not resolve the problem of combined sewer systems in older, urbanized areas. As a result, these combined sewer overflow (CSO) systems are intentionally left to discharge into waterbodies when overburdened by wet weather. The CSO problem was documented as early as the 1960s and gained more attention in the 1990s, when it was openly acknowledgement that retrofitting these systems was phenomenally expensive, but doing nothing about them was equally unacceptable.

Vermont’s CSO problem remains significant despite decades of effort to address it. In 2018, the state reported having spent over $60 million in CSO disconnection since 1990. Vermont put at least $30 million from the American Rescue Plan Act towards it and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act gave $40 million for implementation of the multi-state Lake Champlain Basin Program which includes addressing CSO problems.

Even still, the state’s overall wastewater treatment system is characterized as failing—it’s simply very old—and much investment continues to be needed. A 2023 review of the state of Vermont’s infrastructure explains:

Old infrastructure and operations led to 144 sewer overflow events from 2020 through 2022. From 2018 to 2021, permits issued annually to repair failed wastewater systems grew from 510 to 641.

Vermont’s city of Rutland has it particularly bad. A representative of the city’s public works department explained to the state’s legislature that components of the city’s water system are “undersized and do not function according to modern standards.” To resolve the city’s CSO problem completely would “take additional decades and cost hundreds of millions of dollars,” according to the city’s representative.

It’s not just that Vermont has a failing sewage and wastewater system. Vermont’s dams are also old and need costly attention.

6% of Vermont’s dams are characterized as high hazard. In 2022, the state auditor notified the legislature in big letters that, “Some High Hazard Dams, Including State-Owned, Linger in Poor Condition for Years, Risking Human Lives.” A dam in poor condition is one that has substantial deficiencies “under normal loading conditions.” Another 12% of Vermont’s dams have significant hazard potential, meaning that failure of the dam is not likely to cause loss of life just damage property and infrastructure downstream.

Of the four high hazard dams owned by the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation, three of them are used for flood management and two of these were originally constructed as part of the Winooski Flood Control Projects in 1935, a response to the state’s most significant flooding event on record in 1927.

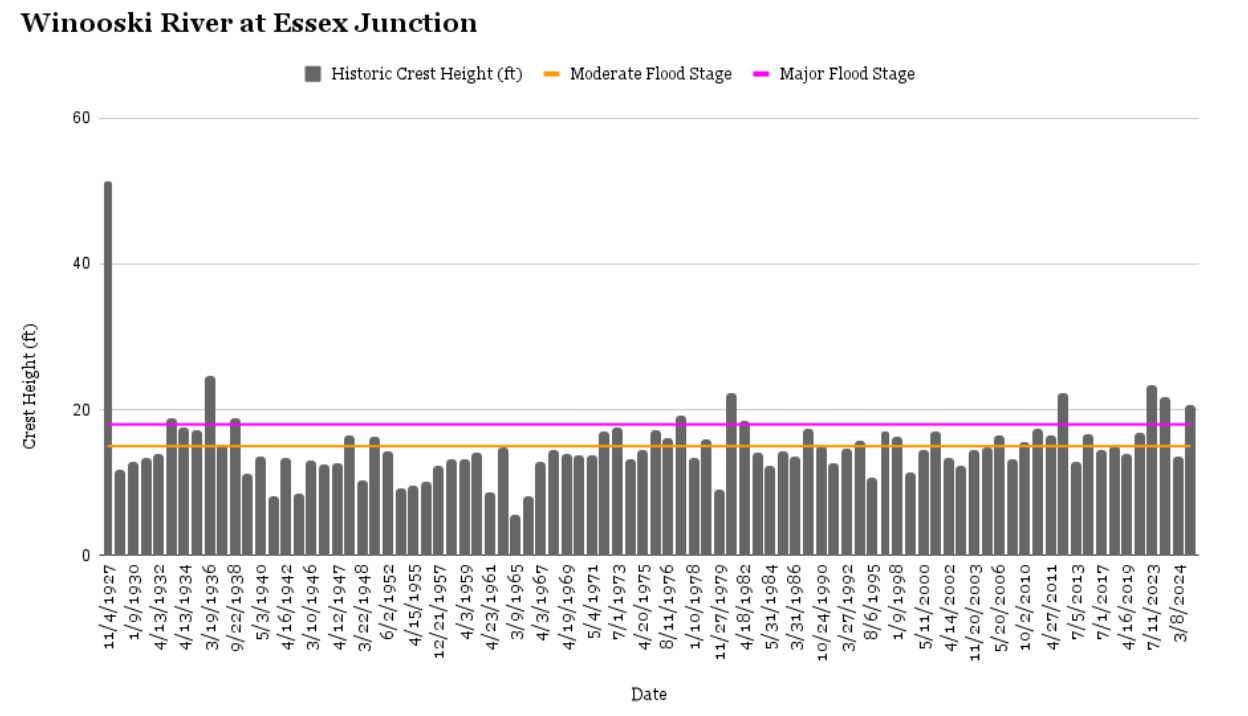

This year and last year, Vermont experienced catastrophic river flooding. However, historic crest height data (the maximum height of the river) indicates that while the observed values are extreme, they are,at least in some locations, not unprecedented. In addition, lower crest levels exceed major and moderate flood stages (the height at which flooding occurs at a specific location).

The chart below shows historic crest heights for Winooski River at Essex Junction, a river gauge in between the cities of Burlington, the state’s biggest city, and Essex Junction.

The yellow line shows the 15 ft moderate flood stage identified by the National Weather Service. There are 32 crest heights that have crossed this threshold over the past 100 years. There are 18 crest heights crossing the pink line that marks the 18ft major flooding stage height with several occurring in the 1930s. The March 1936 flood was part of an historic flooding event across New England as an unusually cold and snowy winter turned into an unusually warm and wet spring.

In short, Vermont’s vulnerability to flooding predates any influence anthropogenic climate change may have on the state’s hydrology.

Vermont: The Degrowth State

Vermont has serious infrastructure challenges. Climate change may exacerbate these challenges, but it certainly didn’t create them. The infrastructure is old and is not equipped to manage the routine extreme weather events over the past century. Part of Vermont’s charm is its historic buildings and towns, but as anyone who has taken care of anything “historic” knows, nothing about it is cheap.

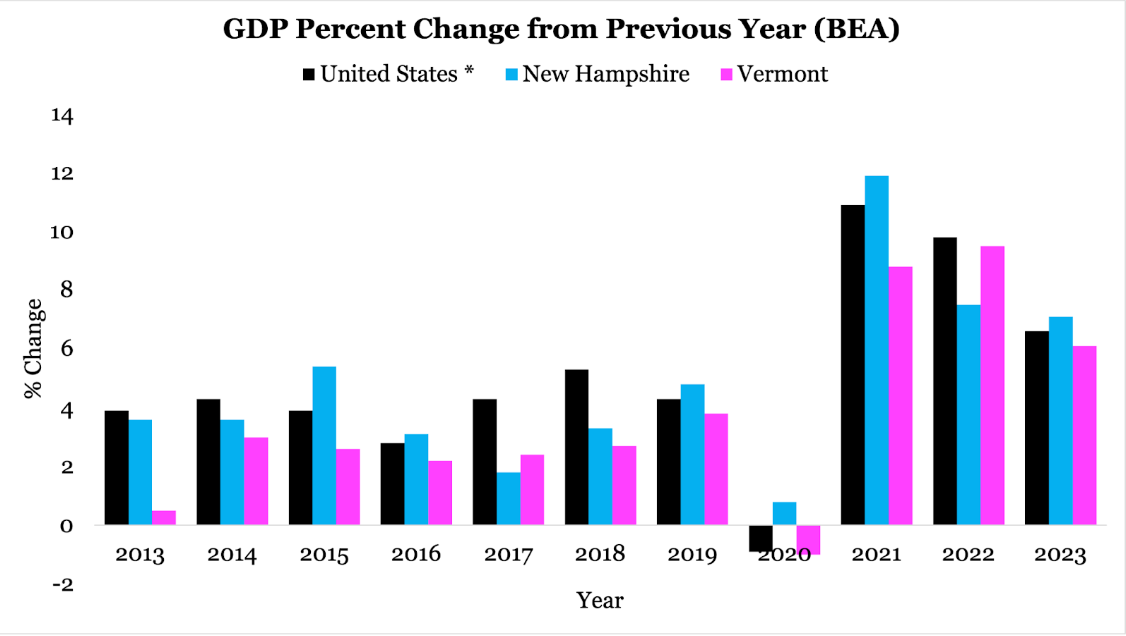

Meanwhile,Vermont has the second smallest population in the nation and the smallest economy. The state’s economic growth regularly underperforms neighboring New Hampshire and the nation. Young Vermonters are leaving the state in droves to search for economic opportunity.

Altogether, Vermont has old infrastructure with serious problems, and too small of a tax base to get the necessary funding to fully address it. But, instead of making policy that could do something about the sewer, stormwater, and flooding issues, Vermont lawmakers are attempting to pin the blame on climate change, and shake down fossil fuel companies to get their needed funding.

Vermont is attempting to hold fossil fuel companies accountable for its own lack of foresight. But any effort by the state to invoice fossil fuel companies for dam upgrades is apt to be met with legal action. There is no telling whether Vermont will be able to get a dime out of the fossil fuel majors, but that might not be the goal. Vermont lawmakers are more interested in making a discursive point about climate change than actually putting every available dollar towards improving their constituents' lives.

Vermonters will find it difficult to sue their way into modernity, and their sewage smells no sweeter than anyone else’s.